Seven is supposedly a special number. Seven days in the week, seven colors of the rainbow, seven notes of the musical scale, Seven Wonders of the World, seven dwarves, 007, 7-11 and so on. So surely there must be some kind of deep Freegold significance to this weekend, because today this blog turns seven! ;D Coincidentally, my hit counter turned all sevens right around the beginning of this year:

In a recent poll of 30,000 people, lucky number 7 was voted most popular. But some people believe it's not so lucky (depending on your perspective of course); that market crashes and economic collapses, some of which can be world-changing events, happen about once every seven years. In fact, last week marked the biggest point drop in the Dow in seven years, both on a weekly and a two-day basis. Thursday the Dow dropped 358 points, and on Friday it plummeted another 531. The weekly drop was 1,017 points, and the last time it plunged more than that was during the worst week of the financial crisis, the week ending Oct. 10, 2008.

Friday's point drop was gigantic at 531, putting it in the top ten of all time (point-wise), but the largest one-day plunge ever was (get this!) 777 points, seven years ago on Sept. 29, 2008. And the largest-ever one-day drop prior to that was almost exactly seven years earlier, a 684 point drop on Sept. 17, 2001. Of course that one followed the bursting of the dotcom bubble and 9/11.

Some of these people even trace this seven-year cycle all the way back to the Great Depression and beyond. For example, seven years before 2001 was the 1994 bond market massacre, and seven years before that was Black Monday, the global stock market crash on Monday, Oct. 19, 1987, which included a one-day Dow plunge of 508 points (by far the largest ever in percentage terms). In any case, seven years seems to be a length of time in which people forget, and bubbles grow freely then pop. Incidentally, the Dow has been going practically straight up now for 6½ years since its low of 6,470 on March 6, 2009. No idea what all of this means, but maybe it's just time for a global systemic reboot. ;D

Anyway, seven years ago today, right in the middle of the financial crisis, I started this blog. And every year on this day, I put up an anniversary post like this one. If you'd like to read about the background and history of this blog, then I recommend reading Four! and Six! And if you'd like to read my candid view on a whole variety of topics covered here, you can read my ten part series at Five! For this one, I'm doing something a little different, because this year I did something different.

This year I decided to focus most of my attention on a private blog called the Speakeasy, which I secretly started 2½ years ago. And on May 10th, I made it available to anyone who wants to subscribe. Since then, there are 11 new posts at the Speakeasy, and only 2 here. So for this 7th anniversary, I decided to give you an excerpt from 7 of those posts, a little teaser so you can see what you're missing. ;D

1. Picassos, Strads, Nobels, Hondas and Bananas

190 Comments

Let me ask you this instead. Why shouldn’t Giants and shrimps buy and sell physical gold at the same price, in the same market? What’s the difference between a single buyer with $44B and 440,000 buyers (0.04% of the population of Europe and the US combined) each with $100K in savings? And what’s the difference between a 25 tonne hoard of gold (which could fit in your bedroom) and 400,000 two-ounce stashes hidden in socks in the back of 400,000 sock drawers?

The reason there’s a difference today (and probably for the last few hundred years) is because of paper gold (before 1971, money was like paper gold and had a similar effect). But that is not an “inherent aspect” or necessary property of the physical gold market any more than paper Picassos, paper Strads and paper Nobels are an inherent part of their markets. It’s an aberration, a departure from the reality of physical markets. Yes, we have people trying to start paper fine art markets today, but that’s only because of the sheer amount of hoarded money sloshing around while it waits for Freegold.

2. Flashback Favorites™

201 Comments

So, what is a Hard Money Socialist? Well, I think he (or she) is an avowed anti-Socialist who expects the Socialist government to adopt his ideology “because it is right in principle,” even though it goes against not only their individual and collective interests, but against civilized society as a whole. The Hard Money Socialist will object to that last part because he believes in and needs something idealistic. As Soupintheattic put it, “I need a hefty dose of what is right in principle.”

Freegold is elegant because it allows for the peaceful coexistence of different ideas of “what is right in principle.” The Socialist apparatchiks are the Debtors’ elite… the political and socioeconomic Robin Hood heroes of societal redistribution. Not ideal having them around, right? Should we get rid of them somehow, or try to change their minds (yeah, good luck with that!), or suppress or control them somehow? Or might it be the ultimate “what is right in principle” idealism to find a way to peacefully coexist with them? That’s Freegold!

The HMS wants to fight and ultimately control the countless Socialists among us, through their submission to a hard money fantasy that only exists in the mind of the Hard Money Socialist (it never existed in reality!). But the Freegolder, or “Physical Gold Advocate” (PGA for short) realizes that simply storing one’s surpluses out of Robin Hood’s reach accomplishes so much more, without any bloodshed or tears. That’s Freegold!

3. Special People

228 Comments

As FOA said above, even his dumb friends can understand this concept. It takes a special person to argue that silver is a preferable or even equal store of value because it is more affordable than gold, and, as FOA said, “it would take a whole world full of special people buying silver to make it work out.” Well, as it turns out, we’ve now tried this experiment and, in the final analysis, there weren’t enough special people to make it work out.

As I said before, I don’t care about silver, and I don’t particularly enjoy writing about it. The last time I did was in 2010. And I know that most of you don’t really care to read these silver posts either. Those of you who have moved on from silver, like me, don’t care about it one way or the other anymore. And those of you who still like your silver, don’t really prefer these kinds of posts, which is why I called it tough love. But between the influx of new subscribers following SRSrocco’s “rebuttal” of my silver post, and several emails I received, it was clear that some silver follow-up was warranted.

It was actually an email from Solitary Monk (who is NOT one of the special people) that convinced me to write another post or two. And for those of you here at the Speakeasy who are still a little bit special yourselves, this is not my final word on silver. I have another post I’m still working on titled “FREE SILVER” (an idea suggested by SM), which will hopefully be done soon and which I’m sure will thrill you all (and crush a few more silver myths in the process)! :D

4. Free Silver

355 Comments

Many people have bought into the argument that, when the metals finally do their moonshot, silver will outperform gold. This view, by definition, implies a reversion of the GSR to much lower levels. And, other than a few “spasmodic” moments along the way, that view is not consistent with what an honest review of history reveals, even though it claims to be.

I know of one long-time gold writer who promotes buying both physical gold and silver, who himself is betting entirely on physical silver, without holding even an ounce of gold. And I know a few individuals who are (or were) doing the same. I shudder at the thought.

It has been said that Freegold is the only narrative in the precious metals sphere that argues solely for physical gold while taking a distinctly negative view on silver’s future usefulness as a wealth reserve. I hope that I have shown in this post that you don’t need Freegold to have a negative outlook on silver as money or wealth.

5. Spanking Greece

267 Comments

Freegold is not a date or time that is possible to predict. It is simply an accident waiting to happen, and at certain times the $IMFS is more accident-prone than at other times. Maybe it’s just me, but all the swirling uncertainty right now reminds me of the summer of 2008. The $IMFS feels accident-prone to me right now in a way it hasn’t really felt since then.

[…]

My point here is that I don’t think there’s going to be any button pushing. I think that in 2008, extraordinary and costly measures were taken and luckily (or unluckily, depending on your perspective) succeeded in buying some more time. And I think that the key measures came not from the US players, but from the BIS. But now, at this point, given the Greek/euro crisis, I don’t think there’s any reason to take extraordinary and costly measures anymore. In fact, as I said above, if I was at the BIS today, I would be very quietly discussing the advantages and benefits of having another global financial crisis at this very moment.

Please don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying “This is it” in my best Jim Sinclair impersonation. I’m simply saying that all the swirling uncertainty in the global financial system right now reminds me of the early part of the summer of 2008. And if it’s still swirling, say, a month from now, then I’ll really be raising my eyebrows and topping off my gas tanks. ;D

6. China’s Gold

680 Comments

For the past year or so, gold bugs near and far have been predicting that when China finally announces how much gold it has accumulated, that the number will shock the world. I never thought that made any sense, and so the number that came out today seems about right to me. I just don’t buy the reasoning put forward as to why the PBOC would be lying about its reserves. Some say they plan to launch a gold-backed RMB. That makes no sense. Others say that revealing a super-sized hoard will rock the markets and send the POG soaring. But like I said, if they could accumulate 10,000 tonnes on the down-low and not affect the physical market or the price, that seems more bearish than bullish to me, and the reasoning doesn’t make sense to me.

To me, the simplest explanation is that they are straight up telling the truth about their official gold reserves. Why would they boast about their unmined gold being the second largest in the world (9816.03 tonnes at the end of 2014), and then lie about official holdings in the humiliatingly-opposite direction? The convoluted logic behind the conspiracy theories attempting to explain such subterfuge doesn’t seem very logical to me.

7. China’s Gold 2

232 Comments

Well, there you have it. As that “Template” was updated for June 30, it should have had at least 19 tonnes on that line if they already had the next month’s gold, so I think the fact that it’s blank supports the notion that they are still accumulating rather than slow rolling a massive stockpile. It should be interesting to watch that line and see if anything shows up there, or if it simply remains blank. But either way, speculation about a massive stockpile was previously just speculation that they simply weren’t saying; now it becomes speculation that they are outright lying on the forms. This makes it even less likely than before, and, I think, supports my view.

Now that I've done all that, I'm feeling a little bit guilty, like I should probably give you a full post on such a momentous occasion as Seven! So I will now roll my seven-sided die to see which one you get. Aaaand… it says you get Free Silver.

Just so you know, this post got mixed reviews. Most of the Speakeasy members couldn't care less about silver, so they don't like me wasting my (or their) time on it. Plus it's an historical post with some measure of boring mixed with way-too-long, so there's that too. But others really liked it. For example, "Viggorish" emailed me this:

Hi FOFOA,

I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed free silver.

It wasn't until I read it for a second time that I realized what a masterpiece this was.

Truly you deserve to pat yourself on the back for this one.

Sincerely,

V

And in the comments, Sam wrote:

This is a great piece of work because it attacks the matter from an angle I haven’t seen before…history. Most silver investors that aren’t sold on the logic based arguments against silver over the years should take note that the historical argument is also pushing against them.

Canadarob wrote:

Basically fofoa has had enough trying to slam silver with the freegold lens so he ditched then lens and said just look at some facts that we already know, silver still sucks. Deal with it.

It also highlights the natural economic energy that has been suppressed in gold.

Gold really is a balloon held at the bottom of Marianas trench.

I still have about 20 ounces of silver though.

And Fred H. wrote:

Thanks to all who contributed to our previous discussion about silver....it caused me to ponder and contemplate some more and resulted in an even better understanding of gold... And since it has been recommended that one should buy gold according to our understanding... I finally hauled in monster boxes of ASE's and bags of US 90% junk halves on a dolly to my local coin dealer.... and exited with roughly three pounds of AGE's. The difference in weight was striking. --I did keep all of my Mercury dimes however--I just like them for some reason.

And like I said, it was the wise old Solitary Monk who recommended this topic as a follow-up to my Silver Dollar post. So here you go all you Silverbugs… enjoy! ;D

Free Silver

Republican campaign poster from 1896 following the silver panic and depression of 1893,

attacking the Democrats' Free Silver movement with satirical slogans like

"Vote for Free Silver and be prosperous like Mexico (where workers earned 25¢ a day)".

As promised, here is Free Silver. My apologies to those of you who thought it would be a silver-based parody of Freegold. Instead, it is real history. How many of you knew there was actually a real political movement called Free Silver about 120 years ago?

It was nothing like Freegold however. The supporters of the Free Silver movement were called "Silverites", and they were mostly Democrats and the populist People's Party, the former left-wing Greenbackers, inflationists in favor of easy money, socialist policy and government price fixing. Their rallying cry was "Free Silver at 16 to 1" at a time when the GSR (the gold to silver ratio) in the free market had reached a high of 32 to 1.

FOA touched on this history in one comment:

Trail Guide (3/1/2000; 17:10:58MDT - Msg ID:26264)

Legal Tender,,,,,,, a long subject

After reading below, one can see that silver came into the picture more so because it would allow "greenback" expansion. The whole context of involving silver into the money system came about from the changing of the "Legal Tender" laws earlier. The thrust of the argument was that people wanted the ability to expand their fiat monetary base........ and the Legal Tender laws were the first way such a change came about.

be back later TG

============================================================

More on the "Greenback movement"

The Panic of 1873 and the subsequent depression polarized the nation on the issue of money, with farmers and others demanding the issuance of additional greenbacks or the unlimited coinage of silver. In 1874 champions of an expanded currency formed the Greenback-Labor Party, which drew most of its support from the Midwest; and after Congress, in 1875, passed the Resumption Act, which provided that greenbacks could be redeemed in gold beginning Jan. 1, 1879, the new party made repeal of that act its first objective. The 45th Congress (1877-79), which was almost evenly divided between friends and opponents of an expanded currency, agreed in 1878 to a compromise that included retention of the Resumption Act, the expansion of paper money redeemable in gold, and enactment of the Bland-Allison Act, which provided for a limited resumption of the coinage of silver dollars. In the midterm elections of 1878, the Greenback-Labor Party elected 14 members of Congress and in 1880 its candidate for president polled more than 300,000 votes, but after 1878 most champions of an expanded currency judged that their best chance of success was the movement for the unlimited coinage of silver.

Notice the phrase "unlimited coinage of silver." That's what the Free in Free Silver means—the free and unlimited coinage of silver by private individuals, meaning you could bring an unlimited amount of silver bullion to the government mint and walk away with minted coins containing the same weight of silver. It's not as important that the mint charged no minting fee or made no seigniorage as it is that there was no limit to the amount of bullion that could be coined and turned into legal tender money, and that it was open to private individuals. In fact, we had virtually free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold from 1792 until 1873, but in 1853 the government began charging one half of one percent to cover the assaying and minting expense of the "free (meaning unlimited) coinage" of gold and silver.

This is an important concept to let sink in, because it makes bullion virtually the same value as legal tender coins. If you find some raw silver in a mine, it is worth its weight in coin, because you can simply take it to the mint and turn it into legal tender coins that can be used to pay off your debt, pay your taxes, etc... But if the mint is doing this for two different metals at a fixed ratio that is different from the going ratio in the open market, then only the overvalued metal will show up to get its new, higher value stamp from the mint.

Just to make this simple, let's say you had "free silver at 16:1" while the going exchange rate in the international market was 32:1. Silver would be the overvalued metal, and therefore only silver would show up at the mint to get its new, higher value stamp. Theoretically, you could borrow one ounce of gold, use it to buy 32 ounces of raw silver bullion, take that silver to the mint and get 32 ounces of silver coins, then pay off your one ounce gold loan with only 16 of those silver ounces, keeping the other sixteen as profit. Then do it over and over again. That's called arbitrage, and it is the basis of Gresham's law.

Such was the bimetallic system established, soon after the foundation of our Government, in 1792. There probably never was a better example of the double standard, one more simple, or one for whose successful trial the conditions could have been more favorable. There was no prejudice among the people against the use of either gold or silver. The relative values of the two metals had been fairly steady for a long time in the past. At the start everything seemed fair. The real difficulty which the future disclosed was one inherent in a system based upon the concurrent use of two metals, each of which is affected by causes independent of the other. The difficulty was certainly not, as some would have us believe, in the selection of a wrong ratio. Knowing, as we now do, that the ratio between gold and silver began to change, as if for a long-continued alteration of their relations, at the very time when Hamilton was setting up a double standard, and learning, as we have, that he declined, from lack of time, to ascertain the market ratio for "the commercial world," we are prepared to find that, as he was wrong in theory, he was also wrong in the ratio he selected with so narrow a view. This, however, is not true. It happened that the ratio he adopted, on the sole ground that it was near to the current relation in the United States, was also, by a piece of good fortune, as near as could be expected to the ratio of "the commercial world." By reference to the Hamburg tables it will be seen that European prices during the four years from 1790 to 1793 (inclusive) gave a market ratio of almost exactly 1:15. Indeed, if Hamilton had taken the European market into account, it is difficult to understand what other ratio he could properly have adopted. As a matter of fact, his legal ratio corresponded with the market ratio when his plan went into operation. As a matter of Hamilton's own monetary skill, it was surely but a hand-to-mouth policy; for a ratio different from that of the commercial world would have been wholly unjustified by correct monetary rules.

We must now accompany the new coinage system in the course of its experience during the first period of its history. The young and promising offspring of Hamilton started well, but soon began to limp, and then to walk on only one leg. We must therefore investigate the cause of this trouble. In calling attention to Chart I it was noticed that the relative values of gold and silver began to change soon after 1780; that relatively to gold the value of silver fell (or, not to prejudge the case, the value of gold rose relatively to silver) until in the last five years of the century the ratio remained in the vicinity of 1:15.5. By continuing the table of figures from 1800 to 1833, the period represented by the chart, it will be possible to see the extent and direction of further changes in this season of trial for the new system. As already observed, the market value, according to Hamburg prices of silver, never rose after 1793 to the ratio of 1:15 (indicated by the horizontal line), within this period which extends to 1833 (although it came nearest to it in 1814 and 1817). After 1820 there was a lower level in the relative value of silver to gold, indicating a more or less permanent change in the relations of the two metals, at a rate between 1:15½ and 1:16. The decline after 1793 was steady, broken by a rally in 1803-1805, and followed by a fall below 1:16 in 1813. These are the simple facts, taken from the most trustworthy sources, concerning the relative values of gold and silver in the first period after Hamilton established his system in 1782. Thus was fulfilled his prophecy: "The revolution, therefore, which may take place in the comparative value of gold and silver will be changes in the state of the latter rather than in that of the former."

Without stopping now to consider the cause of this change in the relations of gold and silver, it will be best to explain the effects of this change—no matter what its cause—upon the coinage of the United States. The situation now resembles that of a man who, having balanced a lever on a fulcrum, and then, after leaving lengthened one arm and shortened the other, should expect the lever to balance on the fulcrum in the same manner as before. We now have an illustration of Gresham's law—that when two metals are both legal tender, the cheaper one will drive the dearer out of circulation. This can not operate, however, unless there is "free coinage," and unless there is such a divergence between the mint and the market ratios of gold and silver as will secure to the money-brokers a profit by exchanging one kind of coins for the other. But, as we have already seen, "free coinage" existed, and a profitable difference between the mint and the market ratios in the United States appeared about as early as 1810.

The operation of Gresham's law is in reality a very simple matter. If farmers found that in the same village eggs were purchased at a higher price in one of two shops than in the other, it would not be long before they all carried their baskets to the first shop. Likewise, in regard to gold or silver, the possessor of either metal has two places where he can dispose of it—the United States Mint, and the bullion market; he can either have it coined and receive in new coins the legal equivalent for it, or sell it as a commodity at a given price per ounce. If he finds that silver in the form of United States coins buys more gold than he could purchase with the same amount of silver in the bullion market, he sends his silver to the Mint rather than to the bullion market. By reference to Chart I, it will be seen that the market value of silver relatively to gold had fallen to 1:16, while at the Mint the ratio was 1:15. That is, in the market it required sixteen ounces of silver to buy one ounce of gold bullion; but at the Mint the Government received fifteen ounces of silver, and coined it into silver coins which were legally equivalent to one ounce of gold. The possessor of silver thus found an inducement of one ounce of silver to sell his silver to the Mint for coins, rather than in the market for bullion. But as yet the possessor of silver had only got silver coins from the Mint. How was he to realize his gain? Will people give the more valuable gold for his less valuable silver coins? To some minds there is a difficulty in understanding how a cheaper dollar is actually exchanged for a dearer dollar. This also is simple. The mass of people do not follow the market values of gold and silver bullion, nor calculate arithmetically when a profit can be made by buying up this or that coin. The general public know little about such things, and if they did, a little arithmetic would deter them. These matters are relegated by common consent to the money-brokers, a class of men who, above all others, know the value of a small fraction and the gain to be derived from it. Ordinary persons hand out gold or silver, when they are in concurrent circulation, under the supposition that the intrinsic value of gold is just equal to the intrinsic value of silver in the coins, according to the legal ratio expressed in the coins. If, under such conditions, silver falls as above described, the money-broker will continue to present silver bullion at the Mint, and the silver coins he receives he can exchange for gold coins as long as gold coins remain in common circulation—that is, as long as gold coins are not withdrawn by every one from circulation. Having now received an ounce of gold in coin for his fifteen ounces of silver coin, he can at once sell the gold as bullion (most probably melting it, or selling it to exporters) for sixteen ounces of silver bullion. He retains one ounce of silver as profit, and with the remaining fifteen ounces of silver goes to the Mint for more silver coins, exchanges these for more gold coins, sells the gold as bullion again for silver, and continues this round until gold coins have disappeared from circulation. When every one begins to find out that a gold eagle will buy more of silver bullion than it will of silver dollars in current exchanges, then the gold eagle will be converted into bullion and cease to pass from hand to hand as coin. The existence of a profit in selling gold coins as bullion, and presenting silver to be coined at the Mint, is due to the divergence of the market from the legal ratio, and no power of the Government can prevent one metal from going out of circulation. Like the farmers with their eggs, under the operation of Gresham's law silver will be taken where it is of the most value (the United States Mint), and gold will be sold where it brings a greater value than as coin (the bullion market).

The above was written in 1885 in The History of Bimetallism in the United States by James Laurence Laughlin (April 2, 1850 – November 28, 1933), an American economist who later helped to found the Federal Reserve System. At the time he wrote the first edition, the debate over bimetallism versus monometallism was less than a decade old, having only really begun nine years earlier:

The experience of this country has been unique. No experiment of bimetallism has ever been inaugurated under circumstances more favorable for its success; and no hostility or suspicion attended its progress. No fairer field for its trial could have been found; and its progress under such conditions makes its history peculiarly instructive. We have had in this country a legal and nominal double standard from the establishment of the Mint in 1792 to the present day, with the exception of the years between 1873 and 1878; and in this period of about ninety years we have had almost every possible experience with our system. Has it proved a success in the past? What lessons does it offer for the future?

It will be remembered that the question of bimetallism has been actively discussed only since the great fall of silver in 1876, and that great animation and warmth have been shown both by its friends and foes. An experience of bimetallism, therefore, under no attacks and under friendly auspices, during the years preceding 1876, for more than three quarters of a century, ought to furnish us lessons which we can readily accept, because they are drawn from results caused by normal conditions, and not vitiated by any suspicion of prejudice against silver. A ship which had proved unseaworthy in fair weather would not be a secure refuge in stormy seasons.

I want to point out a couple more things here before we move on. As you may have already figured out, the two sides of the debate were the Debtors and the Savers, the easy money camp and the hard money camp. And both sides actually had legitimate disputes, disputes which, incidentally, are solved by Freegold. As Laughlin said, the problem with bimetallism wasn't that the fixed ratio was the wrong ratio. The problem was having a fixed ratio at all. Likewise, the problem with the gold standard or monometalism (which came later) was not that the fixed price of gold was wrong, the problem was having a fixed price at all.

Regarding the problem with Gresham's law, that is solved by simply eliminating the "free coinage" of one or both of the metals. Even today, we have coins made of various metals, but because the government now reserves for itself the right to mint coins which it will accept as legal tender, the fact that the face value is higher than the metals' commodity value is of no concern with regard to Gresham's law.

It was also enacted (Sec. 14) that "it shall be lawful for any person or persons to bring to the said Mint gold and silver bullion, in order to their being coined." These words contain the important privilege known as "Free Coinage," by which is meant the right of any private person to have bullion coined at the legal rates. If the Government reserves to itself this right, there would not be free coinage. This is a matter of importance, because through it alone can Gresham's law have an immediate effect. If there is a profit in sending one of two legal metals to the Mint, and in withdrawing the other, with the result of displacing one of the metals in circulation with another, it is necessary, of course, that access to the Mint should be free to any one who sees this chance of profit.

[…]

The operation of the Act of 1878 has been complicated to many minds by the absence of the free-coinage provision, which permits only the Government of the United States to purchase bullion and have it coined into dollars of 412½ grains… It was not apparent why this dollar, which in 1878 contained but ninety cents' worth of pure silver, could, when issued, circulate at par with a gold dollar; nor is it understood why the silver dollar is to-day, at par with United States notes redeemable in gold. There are several reasons to account for this.

[…]

Another fact which maintains the silver dollar at par with gold, and which is of considerable importance, arises from the provision of the act which authorizes the issue of silver certificates. The important consideration, however (and, to my mind, one of the most important provisions of the act), is that these certificates, in the words of the statute, "shall be receivable for customs, taxes, and all public dues."

[…]

It has been a mystery to many people that the silver dollar of 412½ grains should continue in circulation at par, while the trade dollar of 420 grains fell to its intrinsic value, and was not in circulation on equal terms with the Bland dollar, which contains less silver. The coexistence of these two silver dollars added to the complexity connected with the silver question…

At this time, it will be recalled, this coin was a legal tender for sums of five dollars, owing to an unintentional provision of the Act of 1873. Although this law limited its use to small payments, the mere fact of its circulation in the United States called attention to the inadvertence in the Act of 1873, and all legal-tender power was taken away from the trade dollar by a section of the Act of July 22, 1876…

Here we have two silver dollars in the late 1870s and 1880s, one contains almost 2% more silver by weight than the other yet is less valuable because its legal tender status is limited. Both contain less than a dollar's worth of commodity silver, but the one with full legal tender status trades for a full dollar while the "trade dollar" (which was minted with an extra bit of silver specifically for overseas trade in the Orient) is only worth the metal's commodity price.

While it might have been a bit of a head-scratcher in 1885, today it is no big deal. Take the modern quarter. Four quarters currently have a combined melt value of 13¢, yet they trade for a whole dollar. In fact, the Sacagawea dollar, which is 93% copper, has a melt value of only 4¢. 100 modern pennies, on the other hand, and I'm talking about the new ones which are 98% zinc, have a melt value of 50¢, yet we don't see Sacagawea Dollars driving zinc pennies out of circulation.

Imagine, however, if we had "free coinage" of copper and zinc at the mint. It's an extreme example to make a point, but you could buy $100 worth of commodity copper and have the mint make you 2,460 Sacagawea dollars, worth $2,460. $100 worth of commodity zinc, however, would only get you $200 worth of pennies at the mint, so copper would be the way to go and we'd end up with a surfeit of Sacagaweas and a paucity of pennies in circulation.

The problem with gold and silver bimetallism is that, over time, gold tends to rise in value while silver tends to fall. This is probably the biggest point of this post. We're always hearing from the silver bugs how silver is constitutional money and the GSR is bound to return to its historic level of 16:1, but even Alexander Hamilton, Founding Father and the first Treasury Secretary knew it was true when he set the initial fixed ratio at 15:1, overvaluing silver relative to gold:

The establishment of a double standard in the United States is due to Alexander Hamilton. His "Report on the Establishment of a Mint" remains the best source of information as to the reasons for adopting the system which has continued, with a slight break, from that day to this. As was to be expected, the arguments urged at the present time in favor of bimetallism had not occurred to Hamilton. He did not enter into a general discussion of the effects of a double standard, such as we might expect from a modern bimetallist. In speaking of gold and silver, he was emphatic in stating his belief that if we must adopt one metal alone, that metal should be gold, and not silver (at variance, as we have seen, with the views of Robert Morris in 1782); because, said Hamilton, gold was the metal least liable to variation. In fact, we find in his report thus early in our history an expression of that preference for gold over silver, whenever the former can be had, which has since then played no little part among the influences acting on the relative values of the two metals.

"As long as gold, either from its intrinsic superiority as a metal, from its rarity, or from the prejudices of mankind, retains so considerable a pre-eminence in value over silver as it has hitherto had, a natural consequence of this seems to be that its condition will be more stationary. The revolutions, therefore, which may take place in the comparative value of gold and silver will be changes in the state of the latter rather than in that of the former."

This prophecy of Hamilton's was fulfilled to the letter within a few years after the words were uttered.

But in these words also we find the excuse for the adoption of a system of bimetallism which, after the expression of a preference for gold, might have seemed undesirable. If a farmer is seeking for one of two pieces of land, he will be obliged to select that which is within his means. The United States was in the same position as the farmer. There was a general scarcity of specie in the new country, and it was a difficult matter to perform the exchanges with ease. Not only was there no prejudice against silver, but it was the metal most in common use. The whole object of the Secretary was to secure a metallic medium in abundance; silver, being in use, must, of course, be retained, and gold brought in also, if possible. The double standard was preferred, therefore, because it afforded a moral certainty of the retention of silver and a possibility also of adding gold to the money of the land. It would not do, says Hamilton, to adopt a single silver standard, for that would act "to abridge the quantity of the circulating medium." It was hoped to utilize the existing quantity of silver, and yet keep the gold also. Although he preferred a single standard of gold, he must be content to take what he could get; and silver was most easily secured for the new currency. There is, he adds, an extraordinary supply of silver in the west Indies,16 and this will render it easier for the United States to obtain a supply of that metal. He had little conception of the coming effect on his system of this "extraordinary supply" of silver from the South American mines. The scarcity of metallic money was the fact which influenced him in his recommendation of a double standard—a natural scarcity, too, for the country yet felt the effects of the havoc caused by the worthless continental paper which had driven specie out of use. Like the farmer of limited means, who preferred the better although more expensive land, but took the cheaper piece because it was within his reach, Hamilton naturally adopted the poor-country plan, and, in order to secure a metallic currency, took measures to retain silver, the best he could get (with the hope of keeping gold also).

Having, for these reasons, fully decided to adopt a double standard, the Secretary was obliged to face the chief difficulty in the problem—the selection of a legal ratio between gold and silver. Here was the rock on which, as we shall see hereafter, his system was inevitably bound to go to pieces.

Here we see that, from the very birth of the Constitution, silver was the easy money and gold was hard money. But in the bimetallism debate leading up to the "Silver Panic", stock market collapse and depression of 1893, silver's "superiority" (as the poor man's gold ;) was as hotly defended by the easy money camp as it is by today's silverbugs:

Said one: "Why, Senators, we had acquired Louisiana and Florida, we had carried on a war with Great Britain from 1812 to 1815, when we had hardly any gold coin, on the credit of the silver dollar." Nothing, perhaps, can be better than the following eulogium of a Southern Senator on silver: "It enjoys this natural supremacy among the largest number of people because the laboring people prefer it. They use it freely and confidingly. It is their familiar friend, their boon companion, while gold is a guest to be treated with severest consideration; to be hid in a place of security; not to be expended in the markets and fairs. It is a treasure, and not a tool of trade, with the laboring people. A twenty-dollar gold piece is the nucleus of a fortune, to remain hid until some freak of fortune shall add other prisoners to its cell. But twenty dollars in silver dimes is the joy of the household, 'the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.'... Silver is to the great arteries of commerce what the mountain-springs are to the rivers. It is the stimulant of industry and production in the thousands of little fields of enterprise which in the aggregate make up the wealth of the nation." If anything could equal this, it was the utterance of a well-known Northern Senator, Mr. Blaine:

"Ever since we demonetized the old dollar we have been running our Mints at full speed, coining a new silver dollar [trade dollar] for the use of the Chinese cooly and the Indian pariah—a dollar containing 420 grains of standard silver, with its superiority over our ancient dollar ostentatiously engraved on its reverse side.... And shall we do less for the American laborer at home?... It will read strangely in history that the weightier and more valuable of these dollars is made for an ignorant class of heathen laborers in China and India, and that the lighter and less valuable is made for the intelligent and educated laboring-man who is a citizen of the United States."

The aristocratic character of the yellow metal is thus well defined: "Gold is the money of monarchs; kings covet it; the exchanges of nations are effected by it. Its tendency is to accumulate in vast masses in the commercial centers, and to move from kingdom to kingdom in such volumes as to unsettle values and disturb the finances of the world." The following unctuous fondness for silver was put forth by Senator Howe, afterward a delegate to the Monetary Conference of 1878: "But we are told the cheaper metal will drive out the dearer, and gold will be banished from our circulation. Silver will not drive out anything. Silver is not aggressive; it is so much like the apostle's description of wisdom that it is 'first pure, then peaceable, gentle.'... Put a silver and a gold dollar into the same purse and they will lie quietly together."

The above excerpts all came from The History of Bimetallism in the United States, initially written in 1885 and revised in 1896, 119 years ago and 120 years after American independence, so roughly halfway through this monetary experiment we call the US dollar. There's much more to the story of bimetallism and the evolution of US currency than I included in this post, and the entire 278 page book is now in the public domain and free to read here at the Online Library of Liberty.

This next section of the post is an essay (lightly abridged by me) titled The Silver Panic, written in 1978 by Lawrence W. Reed, president of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE). Later, in 1993, he published an 83 page book on the same subject titled A Lesson from the Past: The Silver Panic of 1893, and in 2011 he gave a half-hour webcast seminar titled "The Silver Panic of 1893" which is available on YouTube and well worth the 27 minutes (even though he's an HMS ;) ). You will find the video, for your convenience, at the bottom of the essay.

The Silver Panic

LAWRENCE W. REED

June 01, 1978

"History is little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind," in the opinion of historian Edward Gibbon. While it may be argued that there are numerous triumphs in human affairs to write about, Gibbon’s observation seems to be true. If the typical history text were to be stripped of any mention of war, depression, famine, coercion, tragedy, genocide, scandal, rivalry, and mayhem, the remains could probably be reprinted in a leaflet.

Strangely, the awesome Panic of 1893 seems to have escaped the careful scrutiny and exhaustive research of historians. Though it occurred only eighty-five years ago, it remains an obscure episode in American history. It signaled the beginning of a deep depression. Businesses collapsed by the thousands. Banks closed their doors in record numbers. Unemployment soared and idle millions roamed the streets and countryside seeking jobs or alms. And the country witnessed a spectacular display of political fireworks, now all but forgotten.

For the believer in the free economy, the story of the Panic of 1893 offers a treasure chest of empirical support. The lessons of this tragedy add up to a compelling indictment of government’s ability to "manage" a nation’s money.

Charles Albert Collman observed that "Money trouble was the manifest peculiarity of the long, drawn out Panic of ’93." ¹ Indeed, a breakdown of the monetary system and national bankruptcy were narrowly averted in that year. But money is that great invention which permits the development of a modern exchange economy. How could something so vital to commerce become so troublesome?

Everyone knows that fingerprints are a great aid in placing a suspect at the scene of a crime. The distinguishing characteristics of each individual’s skin patterns make this possible. In the case of the Panic of 1893, the tragedy is smothered with the fingerprints of politicians. "I deem it proper at the outset to state," wrote Charles S. Smith in the October, 1893 North American Review, "that the recent panic was not the result of over-trading, undue speculation or the violation of business principles throughout the country. In my judgment it is to be attributed to unwise legislation with respect to the silver question; it will be known in history as ‘the Silver Panic,’ and will constitute a reproach and an accusation against the common sense, if not the common honesty, of our legislators who are responsible for our present monetary laws." ²

Early Interventions

Contrary to popular impression, government in America has never been totally aloof from the monetary scene. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution grants Congress the power "to coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures." In the century preceding 1893, Congress experimented with two central banks, a national banking system, paper money issues, and fixed ratios of gold and silver.

America’s first cyclical depression occurred in 1819, after three wild years of currency inflation caused by the Second Bank of the United States. When that "money monster" was eliminated by hard money man Andrew Jackson, the economy slumped into depression again and all the maladjustments of the Bank era had to be liquidated. In 1857 the economy had to retrench after a decade of credit expansion on behalf of state governments that had forced their obligations on the state banking systems. In 1873 the post-Civil War readjustment finally corrected the excesses of the government’s rampant greenback inflation. The background of the 1893 debacle is equally interventionist and has some uniquely interesting features which give rise to the label, "The Silver Panic."

Gold and silver rose to prominence as the monies of the civilized world through a process of free and natural selection in the marketplace of exchange. Both circulated as money, though gold was far more valuable. The market ratio between the metals had been roughly 15 to 1 (15 ounces of silver trading for 1 ounce of gold) for centuries. Gold was preferred for large transactions and silver for small ones. The free market had established "parallel standards" of gold and silver, each freely fluctuating within a narrow range in relation to market supplies and demands. Before long, though, government decided it would "help out" the market by interfering to "simplify" matters. The result was another of the many well-intentioned blunders imposed on a populace by force of law: the official "fixing" of the gold/silver ratio. This became the policy of bimetallism.

Under the direction of Alexander Hamilton, the federal government adopted an official ratio of 15 to 1 in 1792. If the market ratio had been the same and had stayed the same for as long as the fixed ratio was in effect, then the fixed ratio would have been superfluous. But the market ratio, like all market prices, changed over time as supply and demand conditions changed. As these changes occurred, the fixed bimetallic ratio became obsolete and "Gresham’s Law" came into operation.

Gresham’s Law

Gresham’s Law holds that bad money drives out good money when government fixes the ratio between the two circulating monies. "Bad money" refers to the money which is artificially over-valued by the government’s ratio. "Good money" is the one which is artificially undervalued. Gresham’s Law began working soon after Hamilton fixed the ratio at 15 to 1, as the market ratio stood at, roughly, 15 ½ to 1. This meant that if one had an ounce of gold, one could get 15 ½ ounces of silver on the bullion market, but only 15 ounces for it at the government’s mint. Conversely, if one had 15 ounces of silver, one could get an ounce of gold at the mint but less than an ounce on the market. So silver flowed into the mint and was coined while gold disappeared, went into hiding, or was shipped overseas. The country was thus put on a de facto silver standard, even though it was the declared policy of the government to maintain both metals in circulation.

Congress in 1834 changed the ratio to 16 to 1, but the market ratio had not changed much, and this time gold was over-valued and silver under-valued. Gold flowed into the mint, silver disappeared, and the country found itself on a de facto gold standard.

With the end of the Civil War inflation, and subsequent readjustment in the depression of 1873, the story of the Panic of 1893 begins to unfold. It opens with the inflationist agitation of the 1870s.

In 1875, the newly-formed National Greenback Party called for currency inflation. The proposal attracted widespread support in the West and South where many farmers joined associations to lobby for inflation. They demanded at first that the government balloon the paper money supply in the belief that such a policy would guarantee prosperity. It was a demand that finds a less shrill but no less potent voice among many economists today.

The greenback inflation of the Civil War era left an indelible impression on many Americans. They were suspicious of plans to revive a policy of deliberate paper money expansion on behalf of any special interest group. In 1875, Congress passed the Specie Resumption Act, declaring it the policy of the government to redeem the Civil War greenbacks at par in gold on January 1, 1879. It was regarded from this point on that in order to protect the redemption of the greenbacks, the Treasury would be obliged to maintain a minimum of $100,000,000 in gold on reserve. The most that the inflationists got was a government pledge not to cancel the greenbacks once redeemed, but to reissue them so that the total number outstanding would remain the same.

Turning to Silver

The attention of the inflationists was then directed at another medium: silver. Robert F. Hoxie, in the Journal of Political Economy in 1893, wrote that the inflationists focused their demands on a silver inflation as a matter of expediency. "They had no love for silver as such," revealed Hoxie, "but it was the cheapest and most abundant substance for which they could gain support, its use would result in more legal tender currency, and its metallic character would in a measure shield the advocates from being stigmatized as inflationists." [4]

The inflationists now became "silverites" and their rallying cry became "Free Silver at 16 to 1." Their influence was sufficient to secure passage of the Bland-Allison Act in February, 1878—the first of the acts putting the government in the business of purchasing quantities of silver for coinage. The Act provided for the purchase by the Treasury of not less than two, nor more than four, million dollars’ worth of silver bullion per month, to be coined into dollars each containing 371¼ grains of pure silver (which coincided with the lawful ratio of 16 to 1, since the gold dollar still contained 23.22 grains of pure gold). These dollars were to be legal tender at their nominal value for all debts and dues, public and private. Paper silver certificates were to be issued upon deposit of the bulky silver dollars in the Treasury.

The free silver forces were dissatisfied with Bland-Allison because it did not go far enough—it did not provide for the free and unlimited government purchase and coinage of silver at 16 to 1. The only silver to be coined would be the two to four million dollars’ worth that the government purchased each month, and the Treasury, while the law was on the books, rarely bought more than the minimum amount.

Silver producers in particular had a vested interest in the state of affairs, for the market price of silver had begun a long-term decline in the 1870s. Securing a government pledge to buy silver at a higher price than could be obtained in the free market was an obviously lucrative arrangement. As the market ratio of silver to gold steadily rose above 16 to 1, the profit potential became enormous.

Bland-Allison Passed Over President’s Veto

Bland-Allison was passed over the veto of President Rutherford B. Hayes. The president, in his veto message, noted that minting silver coins at the ratio of sixteen ounces of silver to one ounce of gold would drive gold out of circulation. The decline of the market price of silver had raised the market ratio at the time of passage of the act to nearly 18¼ to 1. If the mint offered to pay one ounce of gold for just sixteen ounces of silver, then only silver would be minted and the country would be on the road back to a de facto silver standard. In Hayes’ belief, "A currency worth less than it purports to be worth will in the end defraud not only creditors, but all who are engaged in legitimate business, and none more surely than those who are dependent on their daily labor for their daily bread." [5]

When money is left to the free market, its supply is restricted by its scarcity and costs of production. Its value is thus preserved. The declining price of silver on the free market would have erased the profitability of many mines and hence would have prevented a drastic increase in silver currency. But when the government stepped in and bought large quantities of silver bullion for coinage, and paid more for it in gold than was offered in the market, it forced the quantity of the white metal in circulation to exceed its true demand. The government does much the same thing today when it subsidizes peanuts or wheat. The result of this political interference is a chronic surplus of these commodities.

The silverites’ drive for favorable legislation culminated in the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which replaced the Bland-Allison Act. The Sherman Act stipulated that the Treasury had to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver per month [140 tonnes per month], or roughly twice the amount the Treasury had been purchasing under Bland-Allison. Payment was to be made in a new legal tender paper currency, the so-called Treasury notes of 1890, redeemable in either gold or silver at the discretion of the Treasury. The 4.5 million ounces of silver mandated by the law represented almost the entire output of American silver mines. This continuing subsidy to silver producers meant that the government was engaged in a full-blown force-feeding of the American economy. It was only a matter of time before the patient would suffer the pangs of indigestion.

U.S. Out of Step

The action of the United States government in 1878 and 1890 with respect to silver was especially peculiar in light of world monetary events. Germany, immediately after the Franco-Prussian War in the early 1870s, had withdrawn her silver from circulation and adopted a single gold standard. France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and Greece followed by first restricting the coinage of silver and then eliminating it altogether. Denmark, Norway, and Sweden adopted the single gold standard, making silver subsidiary by 1875. In that year, the government of Holland closed its mints to the coinage of silver. A year later, the Russian government suspended the coinage of silver except for use in the Chinese trade. In 1879, Austria-Hungary ceased to coin silver for individuals, except for a special trade coin. This rapid worldwide transition from silver to gold prompted the United States Treasury Department in 1879 to note that "since the monetary disturbance of 1873-78 not a mint of Europe has been open to the coinage of silver for individuals." 6 Yet the United States government, at a time when the value of silver was falling dramatically and when the nation’s trading partners were abandoning the white metal, stepped in to promote silver against gold at the unrealistic ratio of 16 to 1!

One way of looking at silver’s depreciation is to consider the annual average market value of the 371 1/4 grain silver dollar. In 1878, the bullion value of that much silver was about 89 cents; by 1890 it dropped to 81 cents; by 1893, it was worth 60 cents and by 1895 it plummeted to a mere 50 cents. A climate of uncertainty pervaded the world of finance. As Professor J. Laurence Laughlin wrote, "No one could know that contracts entered into when a dollar stood for 100 cents in gold might not be paid off in silver which stood for 50 cents on a dollar. That was the predicament in which every investor found himself who had an obligation payable only in ‘coin’ and not in gold." [7]

In accordance with inexorable economic law, the Bland-Allison and Sherman Acts caused a drain of gold from the Treasury and an inflow of silver. This tampering with the fixity of the standard threatened the Treasury’s declared policy of redeeming greenbacks and other government obligations in gold. And, the disappearance of gold from circulation and from the reserves of the nation’s banks threatened the sanctity of all contracts made in gold. Professor Laughlin observed that no producer "could feel so entirely sure of the standard of payments that he could, without fear or hesitation, make his estimates a few years ahead." [9]

The Flight of Capital

The silver purchases noticeably affected the confidence of foreigners in the American economy. Many British and French investors expected devaluation of the dollar at the least, with complete financial collapse predicted by some. Capital flowed out of the country as these foreigners sold American securities. Even Americans, in increasing numbers after 1890, began exporting funds for investment in Canada, Europe, and some of the Latin American countries, all of which seemed stronger than the United States.

[…]

When President Harrison left office on March 4, 1893, the Treasury’s gold reserve stood at the historic low of $100,982,410—an eyelash above the $100 million minimum deemed necessary for protecting the redemption of greenbacks. Merchants increasingly refused to accept silver in violation of the law and ugly threats of strikes echoed in the nation’s factories.

On April 22 the Treasury’s gold reserve fell below the $100 million minimum for the first time since the resumption of specie payments in 1879. Bankers and investors realized that the Treasury could not indefinitely continue drawing upon the remaining gold reserve to redeem the Treasury notes of 1890 in the attempt to maintain their value. Banks had to brake their easy money habits and began calling in their loans at a frantic pace. More and more investors began to fear that before securities could be sold and realized upon, depreciated silver would take the place of gold as the standard of payments.

By Wednesday, May 3, tension in the commercial community triggered a massive wave of selling on the stock market. The New York Times recorded the events the next day:

Not since 1884 had the stock market had such a break in prices as occurred yesterday, and few days in its history were more exciting. In the industrial shares particularly, there was a smashing of values almost without precedent. In the last thirty minutes the brokers on the floor of the Exchange found the quotations on the board of little use.

Figures posted at one moment were valueless the next. In the industrials which were receiving the most punishment prices were dropping a point at a time. The crowds trading in them were made up of shouting men, who struggled about the floor like football players in a scrimmage.

The Panic of 1893 had begun! On May 4 a stock market favorite, National Cordage Trust, went into receivership. Shortly before the panic, Cordage common stock had sold for $70 per share. The plunge was precipitous, as Charles Albert Collman vividly explains:

In the Cordage Trust circle of the New York Stock Exchange, hats were being smashed, coats torn, cravats ruined. Here was an agony that meant financial life or death to many. Cordage common had gone off 18 points. The preferred had lost 22. Suddenly howls went up from the floor. Those who could distinguish the words, heard the ominous cry: "Nineteen for Cordage!" [17]

The shares, a few moments later, went down to $12. [18]

The Cordage Crash

The Cordage crash was taken as, in Collman’s words, "some occult signal for the halting of enterprise." 19 Plants closed their gates and went quickly into receivership. Unemployment rocketed to 9.6 per cent before year-end, nearly three times the rate for 1892. In 1894, an estimated 16.7 per cent of industrial wage-earners were idle.

From January to July, 1893, mercantile failures totaled a remarkable 3,401, with liabilities totaling $169,000,000. The bulk of the losses came after the first week of May. 0. M. W. Sprague revealed that the "failures exceeded both in number and in amount of liabilities those which had occurred in any other period of equal length in our history." [20]

Bank failures and suspensions were the greatest on record. Most occurred in the South and West, where the evils of a vicious currency expansion had taken root far more extensively than in the rest of the country.

The economy was going through the pains of liquidation. The malinvestments fostered by the Bland-Allison Act and Sherman Act inflation were being sloughed off. The threat to the de facto gold standard was a factor which no doubt complicated things, heightened uncertainty, determined the timing of the panic, and exacerbated the depression, but the chief responsibility for the crisis rested with the attempted force-feeding of the nation’s money supply by government policy. The Commercial and Financial Chronicle said as much on July 8, 1893:

The country is struggling with disturbed credit and the general derangement of commercial and financial affairs which a forced and over-valued currency has developed.. . . Nothing but corrective legislation which shall remove the disturbing law, can afford any measure of real relief. [21]

With the economy in depression, the necessity for eliminating the legislation which precipitated the tragedy became increasingly apparent. On June 30, President Grover Cleveland called for a special session of Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. "The present perilous condition," he declared, "is largely the result of a financial policy which the Executive branch of the government finds embodied in unwise laws which must be executed until repealed by Congress." [22] The ensuing debate in the Congress was a splendid contest, pitting the forces of sound, honest money against the forces of inflation, in which the sound money men calmly answered the question, "What would you put in place of the silver purchases?" with the single, solitary word," Nothing!"

[…]

The repeal bill passed the House on August 28 by a wide margin. President Cleveland’s forceful leadership prompted the Senate to do likewise in October. The New York Times heralded the occasion: "The Treasury is released from this day from the necessity of purchasing a commodity it does not require, out of a money chest already depleted, and at the risk of dangerous encroachment upon the gold reserve." [24]

An indispensable pre-condition to recovery was accomplished with the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. The derangement of the nation’s money was a big step closer to solution, though the road to recovery was long and hard. Not until 1897 did depression give way to revival and prosperity. Repeal of the Sherman Act was, by any measure, an act of congressional repentance. Indeed, it was an open admission that the Silver Panic was the offspring of a profligate, overbearing, and irresponsible government. Historian Ernest Ludlow Bogart summarized the lessons of the Panic of 1893:

It must be said that the net results of this experiment of a "managed currency," that is, one in which the government undertakes to provide the necessary money for the people, were disastrous. For the maintenance of a suitable supply the operation of normal economic forces is more reliable than the judgment of a legislative body. [25]

—FOOTNOTES—

¹Charles Albert Collman, Our Mysterious Panics, 1830-1930 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1968), p. 88.

²Charles S. Smith, " The Business Outlook," North American Review, October 1893, p. 386.

³James A. Barnes, John G. Carlisle, Financial Statesman (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1931; reprint ed., Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1967), pp. 32-33.

4 Robert F. Hoxie, " The Silver Debate of 1890," Journal of Political Economy 1 (18921893): 561.

5 Herman E. Krooss, ed., Documentary History of Banking and Currency in the United States, vol. 2 (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1969), pp. 1921-1922.

6 Ibid., p. 1934.

7 J. Laurence Laughlin, The History of Bimetallism in the United States, 4th ed. (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1900), p. 274.

8 Isaac L. Rice, " Thou Shalt Not Steal," Forum 22 (September 1896—February 1897): 1.

9 Laughlin, p. 269.

10 D. Noyes, " The Banks and the Panic of 1893," Political Science Quarterly 9 (No. 1): p. 15.

11 W. Jett Lauck, The Causes of the Panic of 1893 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1907), p. 80.

12 M. W. Sprague, History of Crises Under the National Banking System (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1910; reprint ed., New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1968), p. 158.

13 Robert Sobel, Panic on Wall Street: A History of America’s Financial Disasters (New York: Macmillan Co., 1968), p. 243.

14 Charles Hoffman, The Depression of the Nineties: An Economic History, Contributions in Economics and Economic History, no. 2 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1970), p. 107.

15 Geo. Fred Williams, " Imminent Danger From the Silver Purchase Act," Forum 14 (September 1892—February 1893): 789.

16 Rendigs Fels, American Business Cycles: 1865-1897 (Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, 1959; reprint ed., Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1973), p. 185.

17 Industrials Were Hit Hard," New York Times, 4 May 1893, p. 1.

18 Collman, p. 164.

19 p. 165.

20 Sprague, p. 169.

21 " Hoffman, p. 229.

22 Congress to Meet August 7," New York Times, 1 July 1893, p. 1.

23 James McGurrin, Bourke Cockran (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948), p. 135. p. 138.

24 "Need Buy No More Silver," New York Times, 2 November 1893, p. 1.

25 Ernest Ludlow Bogart, Economic History of the American People (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1937), p. 693.

1893 sounds a lot like 2008 to me, if you recall how things got progressively worse, culminating in TS really HTF mid-summer. Stocks were crashing, banks were closing, people were panicking, railroads and other companies were failing and unemployment was rising. By July, President Cleveland called Congress back for a special summer session to begin on August 7 (Congress wasn't due back until September) to repeal what many saw as the root of the problem, the Sherman Silver Purchases Act of 1890.

The Sherman Silver Purchases Act of 1890 was meant to raise and support the market price of silver. But it just doesn't work that way.

In his address to Congress on August 8 at the special session, Grover Cleveland said the following:

"Values supposed to be fixed are fast becoming conjectural, and loss and failure have invaded every branch of business.

I believe these things are principally chargeable to Congressional legislation touching the purchase and coinage of silver by the General Government.

This legislation is embodied in a statute passed on the 14th day of July, 1890, which was the culmination of much agitation on the subject involved, and which may be considered a truce, after a long struggle, between the advocates of free silver coinage and those intending to be more conservative.

Undoubtedly the monthly purchases by the Government of 4,500,000 ounces of silver, enforced under that statute, were regarded by those interested in silver production as a certain guaranty of its increase in price. The result, however, has been entirely different, for immediately following a spasmodic and slight rise, the price of silver began to fall after the passage of the act, and has since reached the lowest point ever known." Source

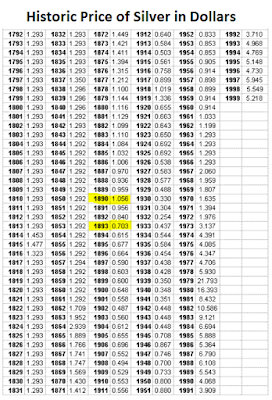

The Sherman Silver Purchases Act was repealed by the House in August, and by the Senate in October, but that was neither the end of silver's fall from grace nor the last time our government would try to support its declining price at the behest of the easy money camp. At 16:1, the market price of silver should have been $1.29 per troy ounce. In 1893, it had fallen to 70¢ per ounce, but by 1932 it had declined to its all-time low of only 25¢ per ounce. With gold jumping from $20 to $25 per ounce on the open market, the GSR was also at its all-time high of 100:1.

Up until the London gold pool in the 1960s, the market price of gold bullion never had to be defended by a government in either direction. Gold was simply money (or real wealth as I like to say), and the various national currencies were defined as a certain weight of gold. So rather than defending the price of gold, it was the price of the various currencies (in gold) that had to be defended occasionally, and if the currency was overpriced, gold (real wealth) would simply flow away like it did from the US Treasury in 1890-93.

With bimetallism in the US, when there was a problematic discrepancy between the legal ratio and the market price of bullion, they would either change the weight of silver in a dollar (not change the weight of gold because gold was the primary money and silver was subsidiary) as they did in 1834, or try to raise the price of silver bullion in the open market as they did from 1887 to 1893. You can see in the following table how the market price of gold bullion was virtually unchanged until 1931.

In 1933, however, with silver at only 25¢ per ounce and the GSR at a stunning 100:1, President Franklin D. Roosevelt did some incredible things. The Thomas Amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, an amendment drafted by Senator Elmer Thomas (D) of Oklahoma attaching silver to FDR's New Deal farm relief bill, allowed foreign debtors to pay the US Treasury in silver coin at 50¢ per ounce, twice the going rate. This helped boost the price of silver up to 44¢ per ounce.

Then, for the first time in more than 140 years, he changed the definition of a dollar in gold terms while leaving the dollar in silver terms unchanged. Here's an excerpt from FDR's "Proclamation 2072 - Fixing the Weight of the Gold Dollar":

Whereas… the present weight of the gold dollar is fixed at 25.8 grains of gold nine-tenths fine…

…the President is authorized – By proclamation to fix the weight of the gold dollar in grains nine-tenths fine and also to fix the weight of the silver dollar in grains nine-tenths fine at a definite fixed ratio in relation to the gold dollar at such amounts as he finds necessary from his investigation to stabilize domestic prices or to protect the foreign commerce against the adverse effect of depreciated foreign currencies, and to provide for the unlimited coinage of such gold and silver at the ratio so fixed…

Whereas, I find, from my investigation, that, in order to stabilize domestic prices and to protect the foreign commerce against the adverse effect of depreciated foreign currencies, it is necessary to fix the weight of the gold dollar at 15 5/21 grains ninetenths fine,

Now, Therefore, be it known that I, Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, by virtue of the authority vested in me by section 43, Title III [Title III was the Thomas Amendment], of said act of May 12, 1933, as amended, and by virtue of all other authority vested in me, do hereby proclaim, order, direct, declare, and fix the weight of the gold dollar to be 15 5/21 grains nine-tenths fine, from and after the date and hour of this Proclamation. The weight of the silver dollar is not altered or affected in any manner by reason of this Proclamation." Source

He also, of course, made it illegal to hoard gold beyond a few coins and called in all of the gold in the banking system, effectively eliminating the domestic market for gold. All of this helped boost the price of silver another 15¢, up to 58¢ in 1935, but by 1939 it was back down to 35¢ an ounce. To quote Grover Cleveland, "following a spasmodic and slight rise, the price of silver began to fall."

Of course the nominal price of silver in fiat currencies will rise over time as governments debase their currencies for various reasons, but I think the real story here is that the price of silver in real money (or real wealth as I like to say), gold, is the story of a very useful metal of declining monetary value. Even without Freegold as a premise, if you take an honest look at real history, there is no reason to expect a "reversion to the mean" of 16:1.

It was known even before we had the Constitution that silver was the more useful metal of the two (more useful in industry). A 1785 report from the Continental Congress, four years before the Constitution went into effect, said: "Silver is not exported so easily as gold, and it is a more useful metal." Even Alexander Hamilton knew of "that preference for gold over silver, whenever the former can be had," whether "from its intrinsic superiority as a metal, from its rarity, or from the prejudices of mankind"!

I hope I am making it unmistakably clear that Free Silver was a political movement of the Debtors' camp, not the Savers. I imagine some of you might still be thinking: "Well, silver is still a (quote-unquote) 'precious' metal, real, constitutional and historical money, and therefore it is harder money than pure paper, therefore the Silverites who wanted Free Silver must be in the hard money camp." But if they had been for hard money, then they would have been happy with the free, unlimited coinage of their silver at the going free market price ratio of silver to gold like it was in the beginning, in 1792. But that's not what they wanted. They wanted Free Silver at 16:1 as a repudiation of debts. Here's Laughlin on the two camps:

The silver advocates were largely the advocates of expansion. Said Mr. Ewing in the House: "Mr. Speaker, nine tenths of the people of the United States demand the unlimited coinage of the old silver dollar with which to pay their debts… not only unlimited coinage, but coinage of silver bullion owned by citizens for immediate use in business." … An answering echo [from the other camp] came from the Senate: "In many sections of the country it is now questionable whether, under the most favorable conditions we can hope for in the future, there can be any escape from the embarrassments that surround the debtor class except through bankruptcy.... In view, then, of the condition of affairs, it seems to me that any measure that tends in any degree to uphold the value of property, or to prevent its further depreciation, ought to meet the support and concurrence of all." … But, perhaps, the coarsest expression of this sentiment [from the easy money camp] was reserved for the lips of Mr. Bland, who declared: "I give notice here and now that this war shall never cease, so long as I have a voice in this Congress, until the rights of the people are fully restored and the silver dollar shall take its place alongside the gold dollar. Meanwhile let us take what we have and supplement it immediately on appropriation bills, and, if we can not do that, I am in favor of issuing paper money enough to stuff down the bondholders until they are sick [Applause]."

Much more evidence could be cited, if more were necessary, to show that, in the minds of a very large number of men who urged the passage of the Bland bill, there was a hope that they might expand the currency by its provisions; and even that silver dollars would be extensively added to the circulation and create the same effects. …

In fact, one is struck, on every page of the debates, with the radically different temper in which the subject of the coinage was treated in 1878 from that shown in 1853, or even in 1792. There is not a shadow of a doubt that, had silver not fallen in value in 1876, so that a dollar of silver had not become worth much less than a gold or paper dollar—and so afforded a new device for meeting existing debts, which at the same time was technically coin—we should never have heard much of the silver agitation. It was born of a desire for a cheap unit in which to liquidate indebtedness. And the demand for the free coinage of a dollar containing only ninety cents of intrinsic value received the support of all who had before marched in the ranks of the inflationists. Silver had got into politics, and was henceforth discussed politically, not scientifically.

[…]

The free coinage of the silver dollar would have given to each man who brought silver bullion to the Mint the benefit of the whole difference between the intrinsic value of 412½ grains of silver and the nominal legal-tender power given it by its face value; and this difference was to be used by any debtor to deliver himself from his obligations to just that amount without returning to his creditor any purchasing power therefor. This was repudiation of debts on a scale to the dollar marked by the descent in the intrinsic value of silver below its face value.

Laughlin also gives us a brief summary, or what he calls "a very brief résumé of the main arguments of both parties to the controversy." The two parties are the Bimetallists and the Monometallists, or the easy money camp and the hard money camp as you will see, also known as the Debtors and the Savers. First he gives us the basic arguments of the Bimetallists who were the easy money Silverites of the 1880s and 1890s:

I. BIMETALLISM has been proposed under two such widely differing conditions that the following general division of arguments may properly be adopted:

A. National Bimetallism.

B. International Bimetallism.