Year of the ________?

You'll have to go to the Speakeasy to read the New Year's post, but here I'm giving you three sample posts from earlier in the year. The first is from back in July, titled Will Basel III End the LBMA? Update!, and it is timely because the Basel III rules, which some said would end the paper gold market and usher in a physical-only market, are supposed to kick in today, for the UK (which obviously includes London and the LBMA).

Also, this past year I had a series of hyperinflation update posts, titled Hyperinflation Update, Hyperinflation Update Update, Just Another Hyperinflation Update, and Just Another Hyperinflation Update #2. A section of the new New Year's post could be considered the fifth in that series. I'm going to give you the first two here, from back in April and May, so enjoy, and have a happy new year!

7/9/21

Back in May, I wrote the post: Will Basel III End the LBMA? To recap, people had been asking me to comment on a number of articles that suggested Basel III would indeed end the LBMA and destroy the paper gold markets. The PRA or Prudential Regulation Authority, UK’s banking regulator which is actually just part of the Bank of England or BoE, had put out a CP or Consultation Paper on the "Implementation of Basel standards" back in February, and the LBMA had responded on May 4th, one day past the deadline.

I went through the LBMA's response in detail in my post, and my conclusion was encapsulated in this sentence:

The abstract for this post is that I basically agree with the arguments the LBMA made in their response, and in the absence of something “unforeseen” happening in the meantime, I think they’ll work.

It turns out I was right. The LBMA paper proposed three solutions, and the PRA/BoE granted one of them. I summarized the three proposals like this:

The LBMA paper basically proposes three solutions, any or all of which are valid in my opinion. One is to simply change the classification of “gold” (i.e., “unallocated gold”) from a non-liquid asset to an HQLA or high-quality liquid asset, thus dropping its RSF factor to 0%. Another is to treat bullion banking as what it de facto is, a separate currency banking system denominated in gold ounces such that unallocated physical is essentially the cash in the system. This would separate it from the need for “stable dollar funding” for gold-denominated assets, because “no other currency besides gold [is] used in these transactions.”

The third proposal is to do what Switzerland is proposing, and “treat precious metals assets held by banks resulting from precious metals loans as interdependent assets and liabilities,” which “would exclude the majority of precious metals assets held by Swiss banks from the NSFR calculation.”

They shot down the first two, but granted the third in a limited way. Here's the relevant section from the LBMA proposal back in May:

5. Proposals

5.1 Clearing and Settlement

[...]

Interdependent assets and liabilities: We note that Switzerland proposes to treat precious metals assets held by banks resulting from precious metals loans as interdependent assets and liabilities (therefore relying on an equivalent of Article 428f(2) CRR II). This would exclude the majority of precious metals assets held by Swiss banks from the NSFR calculation.

We believe that 428f CRR II may offer a viable means to at least safeguard clearing and settlement for precious metals transactions. We believe that the system should be considered a market utility without which precious metals transactions would take many days to settle, resulting in increased settlement risk for all market participants. Within the four clearing bank members of LPMCL that provide this service, there will always be a corresponding asset and liability for every transaction that is placed through them for clearing purposes. Note that this is not a novation agreement whereby a central counterpart takes on all credit risk but is simply the mechanism where a client instructs the clearing bank to make or take delivery of gold and the clearing member bank therefore checks that the other counterparty can indeed make or take delivery.

It is therefore proposed that the PRA exclude the clearing and settlement of precious metals transactions, from the NSFR.

Today the PRA/BoE released Policy Statement PS17/21 – Implementation of Basel standards. Here's the link to the actual PDF. And here's the relevant section, from page 65 of the PDF:

13.90 Respondents thought that the PRA’s proposed rules could have a material impact on both firms and the precious metals markets more generally. Three respondents considered the proposed approach could result in increased costs for end users, and potentially result in firms exiting the market for these products. Three respondents suggested a number of alternative treatments of commodities-related transactions that they considered to be more appropriate. These included treating gold as a HQLA, treating gold as a currency, applying lower RSFs to precious metal assets associated with deposit-taking and clearing activities, applying the IA&L permission, and excluding physical unencumbered stock backing customer deposits from the NSFR.

13.91 The PRA has considered the responses and decided to amend its approach to precious metal holdings related to deposit-taking and clearing activities. The PRA has introduced an interdependent precious metals permission for which firms may apply in respect of their own unencumbered physical precious metal stock and customer precious metal deposit accounts.73 When the permission is granted, firms would apply a 0% RSF factor to their unencumbered physical stock of precious metals, to the extent that it balances against customer deposits. The PRA has decided not to amend its approach for other aspects of the treatment of commodity-related activities. The PRA considers its overall approach to commodities in the NSFR to be generally appropriate. The PRA notes that it is able to waive or modify rules under section 138A of FSMA where a firm can demonstrate to the PRA’s satisfaction that the application of the unmodified rule would impose an undue burden on a firm, or would fail to achieve its intended purpose, and where modifying it would not adversely affect the advancement of the PRA’s objectives.

73 Liquidity (CRR) Article 428f(2)–(3)

I'll leave you with a few thoughts...

First, it makes perfect sense, doesn't it? If a bank has its own unencumbered physical gold "stock" in its vault, and it is offset by gold deposits, aka gold-denominated liabilities, then it should be treated the same as physical cash in the vault offset by dollar-denominated liabilities (or pounds or whatever). And that would be a 0% risk weighting.

In fact, it's even spelled out as such, by the BIS, in the final Basel III document. From page 28:

A 0% risk weight will apply to (i) cash owned and held at the bank or in transit; and (ii) gold bullion held at the bank or held in another bank on an allocated basis, to the extent the gold bullion assets are backed by gold bullion liabilities.

So it's really a no-brainer, and one wonders why it even needed to be proposed, granted and stated as such. But here's the interesting part: it's not automatic. It's a "permission" that must be requested by the bank and granted by the PRA/BoE. On top of that, it is surprisingly specific in that it applies only to unencumbered owned physical stock ("their own unencumbered physical precious metal stock").

Normally, they (meaning the LBMA, central banks, bullion banks, the WGC, etc.) talk about gold in vague terms, like "bullion" or "metal" which make it sound like everything they do is physical, when the reality is that the vast majority of it is not. But here the BoE used wording that is so specific it can only apply to actual physical reserves. I find this interesting.

Take a look at this paragraph from my post back in May:

The Basel III Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) or 85% RSF applied to unallocated gold assets does not only apply to the bullion banks’ reserves, it applies to all gold denominated assets on their balance sheet. But again, this doesn’t have to be as complicated as it sounds. Just like there’s no practical distinction between an unallocated gold deposit or liability that was created by depositing physical gold into the vault and one that was purchased using dollars, there is no practical distinction as far as the banking regulator is concerned between a gold-denominated asset and a gold-denominated reserve.

Well, here the banking regulator has drawn the distinction, and defined reserves very specifically. Not only that, but the bank has to request permission to apply the 0% risk weighting to its own unencumbered physical gold, and that permission has to be granted. In other words, the BoE wants the bullion banks to declare how much unencumbered physical gold they have.

I don't know if this is actually going to happen, or even if it's what the BoE is aiming for, but I do find it interesting, because I don't think the bullion banks have any unencumbered physical gold. Maybe they have a little, but to be more specific, I don't think they have as much as they should have based on the clearing data they've been reporting, which is about 600 tonnes.

Remember, each pallet is one tonne, so between HSBC, JP Morgan and ICBC Standard Bank, the three vaulting custodians, they should have at least 600 of these pallets sitting around totally unencumbered, not allocated, not in any ETF, not leased, wholly owned slack in the flow, and I'll bet you they don't. BTW, there are only about 50 shown in this picture, so we're talking 12 times this amount, and that's just for daily clearing:

As I have explained many times, I suspect they have been using GLD shares for clearing rather than unencumbered physical. They can do this because only bullion banks (the GLD APs) can actually own GLD shares. Shareholders that think they own shares really only own bank liabilities denominated in GLD shares. The GLD trading market is a secondary market (see this post for more). The primary market is the bullion banks because shares are in street name only, and since GLD is fully reserved in physical in the HSBC vault, it is likely being used for interbank gold-denominated clearing by the LPMCL, if/when it doesn't have enough "owned unencumbered physical precious metal stock" for clearing.

If I were a bullion bank, I would have kept my mouth shut and not responded to that February Consultation Paper. They didn't gain anything in the process. In fact, they lost something. They lost the ability to pretend they have 600 pallets of unencumbered unallocated physical gold just sitting around. And any pallets that they did happen to have, they could have applied a 0% risk weighting to anyway, without asking permission, based on both simple logic and the wording in the BIS Basel III final document, as I pointed out above. As they say, sometimes it's better to ask forgiveness than permission.

Reuters, who reported this today, contacted the LBMA clearing banks for comment. JP Morgan declined to comment, and HSBC, ICBC Standard and UBS didn't respond.

Ooh, that reminds me of something I wrote back in May: "It’s almost as if the BoE set this up, and told the LBMA to submit that paper." Hmm. 🤔

Sincerely,

FOFOA

ADDENDUM: Here is some more explanation of this post from the comments...

"FOFOA

This topic is always a bit opaque to me, so I might be on the wrong track.

Does this give them the opportunity to not apply for the 0% rating, therefore not disclosing the true amount of their unencumbered gold, and just living with the 85% default rule?

If so, is that significant?"

Hello Lisa,

No, I don't think this is a big deal. And you're right, it doesn't force them to disclose anything.

What I find interesting is that the whole exercise didn't do much for the LBMA. It seemed somehow contrived. It reminds me of this, from 2016:

The second thing about this BOE/subcustodian disclosure which I found puzzling was the request from the SEC to the WGTS, which ostensibly motivated the disclosure. It was in a letter dated 3/29 and filed on 3/30. Here's the official pdf of the letter. Simply stated, it asked GLD to "please disclose the amount of the Trust’s assets that are held by subcustodians." One day later (even though they were given ten business days to respond), dated 3/30 and filed on 3/31, the final day of the quarter in which the disclosure appeared, GLD's response letter replied, "We will, to the extent material, disclose in future periodic reports the amount of the Trust’s assets that are held by subcustodians. Please be advised that during fiscal 2015, no gold was held by subcustodians on behalf of Trust."

No big deal, right? Except that GLD has been disclosing subcustodian holdings in every 10-Q and 10-K filing since 2009! Here, here, here and here are just a few random examples which show that the SEC's letter was as unnecessary as GLD's response (really the WGC's response if you look at the letterhead) was strange. Just do a CTRL-F search for the word subcustodian in those filings, and you'll see that each one says, "Subcustodians held nil ounces of gold in their vaults on behalf of the Trust."

Of course now, in hindsight, it appears that those statements referred only to the last day of the quarter, that specific day of reporting, which wasn't obvious or even implied prior to the 4/29/16 10-Q filing, which for the first time differentiated "during the quarter" from the end date with regard to subcustodian holdings. Think about this, because I think there is a simple and plausible explanation.

The SEC's letter doesn't make sense the way it is written, at least not to the casual reader, because it asks for something that GLD had already been doing for seven years. Neither does GLD's response make sense, because it should have brought attention to the fact that GLD had been reporting nil ounces held by subcustodians since 2009. Both letters do make sense, though, if both letter-writers knew they were referring to "during the quarter" as opposed to on the end date of the quarter. But because this difference wasn't explicit in either letter, they only make sense if they were essentially staged, filed in order to explain and justify a change in reporting whose real motivation lay elsewhere. Indeed, both letters barely squeaked in before the end of the quarter.

If this explanation is correct, then it raises the question of why the change in reporting needed to happen for that specific quarter. There are basically three players involved—the SEC, GLD and the BOE. Of the three, the BOE is the new one, so perhaps it was the BOE that, for whatever reason, wanted to get this subcustodial disclosure on the record. Perhaps a request by the BOE was the real motivation.

What happened was that GLD added a big chunk of gold in February that it borrowed from the BoE. 29 pallets to be exact. In fact, the pallets of bars stayed in the BoE vault and GLD just added the bar numbers to its list, so the BoE became a temporary "subcustodian" for GLD. And someone wanted to make sure this was disclosed on GLD's quarterly SEC filing.

The quarter ended on 3/30, and on that day, an attorney for the SEC filed a letter addressed to GLD c/o the WGC, which gave them ten days to respond. They responded the very next day, and based on the content of the letters, they were clearly just for the record. The real question is what prompted them, and the only answer that makes sense is that the BoE wanted to make sure that GLD disclosed this fact in its quarterly filing.

So the letters were essentially staged to explain the appearance of the disclosure that the BoE was suddenly a subcustodian for GLD as being the result of a demand from the SEC. But how would the SEC even know this had occurred? They wouldn't, unless either the BoE or GLD told them. I don't pretend to know why the BoE would have orchestrated this disclosure, but it does give us an insight in to how the BoE may operate with regard to the bullion banks.

I'm getting a similar feeling with this Basel III thing.

This is just speculation, but say the BoE suspects that the LBMA is out of reserves, perhaps because they've been borrowing from the BoE again. Why would the BoE care? Well, remember that the BoE had to clean up the mess after one of the London bullion banks collapsed in 1984, and in the aftermath, it assumed the supervisory role over the whole London bullion market and demanded that the participants create a formal body to represent them as a group, the LBMA.

The LBMA is really just a trade association for the bullion banks, like the WGC is for the miners. The WGC is not a mine itself, and the LBMA is not a bullion bank itself, so one can imagine that it's easily manipulated by, say, its supervisor or regulator. Enter that response letter of May 4, signed by Ruth Crowell of the LBMA (not a bullion banker herself, not even a banker, in fact, just before joining the LBMA in 2006 she interned for the UN Commission on Human Rights according to her LinkedIn page), and David Tait of the WGC. Who do you think told them to write it? Someone at JP Morgan? Or someone at the PRA, aka the BoE?

It's also interesting to me that it appears to have been submitted a day after the deadline for submitting responses. Like it was a last-minute thing, and the BoE said don't worry about the deadline, we'll still take it under consideration.

I'm not trying to make a big deal out of this, just pointing out that things are not as they seem on the surface.

Take the Reuters article. The headline is "Britain carves out exemption for gold clearing banks from Basel III rule." It was written by Peter Hobson, a precious metals reporter for Reuters. Who do you think fed him the story?

It has been updated since yesterday. He added a response from an LBMA lawyer, and one from UBS:

"This is one of the key points that what we've been asking for all these years," said Sakhila Mirza, the LBMA's chief counsel. "Clearing will be exempt."

A spokesperson for UBS said: "UBS welcomes the PRA's decision, which supports stability in bullion clearing and avoids disruption to the London market."

Another update is that HSBC declined to comment. So JP Morgan and HSBC both declined to comment, and ICBC Standard still hasn't responded to the request. Only UBS responded, but UBS is not an LBMA custodian.

So it wasn't the banks or the LBMA that fed him this story (and the spin he put on it). I think it was someone at the BoE. I don't think he just stumbled upon it, because it's two paragraphs on page 65 of a dense 86-page document that's 99% about regular banking, and less than 1% about bullion banking. And Peter Hobson writes about precious metals, not banking.

It's all just a little weird. I showed you what the document actually says. It's quite specific. It's almost as if the people who commented from the LBMA and UBS didn't actually read the document, but only commented on the spin provided by the BoE via the Reuters article.

I hope that clears it up. There's no bombshell in this post. Nothing earthshattering. Just a little more color for the view.

"Interesting post, Fofoa. So if the Swiss proposal exposes the fact that there is much less unencumbered gold in the bullion banking system than previously reported, does it’s adoption change your views about the underwhelming effects of Basel III on the banks, i.e. will that cause any change in banking practices and/or have any effect on paper versus physical gold prices?"

Hello Jman,

Notice that I wrote in the post that they granted the Swiss proposal in a limited way. The Swiss proposal as it was presented in the LBMA response paper refers to "precious metals assets held by banks resulting from precious metals loans," and would therefore "exclude the majority of precious metals assets… from the NSFR calculation."

The BoE limited it to only unencumbered physical.

The BoE also included the reference to Article 428f(2) CRR II from the Swiss proposal. All that says is this:

"the following items shall be reported to competent authorities separately in order to allow an assessment of the needs for stable funding:

(f) other precious metals;"

This is the interesting part because it requires an assessment by the BoE of any unencumbered physical the banks intend to count as a 0% risk-weighted asset. That's not something that will ever be published, so it's not going to expose anything to anyone but the BoE. It's more like a warning, or a shot across the bow of the bullion banks by the BoE, that they already know.

Again, I'm not saying that anything big will come of this. The LBMA is going to fail on its own. Basel III is nothing in this case except for a tool used by the BoE to put the bullion banks in an awkward position. Why the BoE is doing this (if this is what they're doing) and what they have planned, I have no idea. Like I said, I expect the LBMA to fail when the $IMFS financial system collapses. But it's interesting to see these moves for what they are, rather than what they appear to be on the surface.

That headline, "Britain carves out exemption for gold clearing banks from Basel III rule," seems like pure spin to me. And it appears like it was handed to the reporter by the BoE (or the PRA which is the BoE). So on the surface, it looks like the LBMA won. But I dug deeper and sought out what the BoE actually wrote, and it's a little different than the headline. I'd say HSBC and JP Morgan were smart not to comment. But no, don't expect anything to come of this that you'll get to see.

"Thank you for this update FOFOA.

Do I understand you correct that we will possibly find out how much physical the bullion banks will really have themselves unencumbered?

So the important question also I think

Does this have any implications regarding their possibility of the delta hedging practice and all the other “fugazi” they do?

Thank you

Koba"

Hello Koba,

No, I didn't mean to give the impression that this will force them to come clean publicly. Nosh posted the Reuters article yesterday, and with a little digging, I found it to be somewhat misleading. So I applied my lens to this thing, and presented the view. That's all. It's totally consistent with my view that the LBMA is running on fumes and will collapse quite easily when tshtf. ;D

Sincerely,

FOFOA

4/25/21

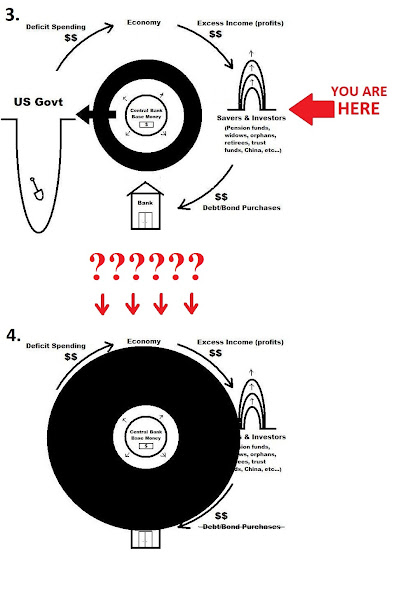

A year ago, on 4/24/20, I used this graphic to illustrate where we were on the road to hyperinflation, and I think it's time for an update:

Before I give you the update, I should explain the graphic. It's not something you'll find in any textbook. They are illustrations that I created back in 2010 to show how I visualize the death of the $IMFS in my mind.

Think of them as end-of-life stages, or signs that death is near. They are not meant to show causation, why the $IMFS is dying, or what is killing it, but rather to give you snapshots of what's to come.

I find it interesting that I'm still impressed with my work on these eleven years later. As simple as they are, I must have put some serious thought into them. So I'm going to try to explain them a little better than I did last year.

The first frame is how the $IMFS operates under normal conditions, say, ever since the 1970s. Debt and savings grow in concert, feeding on each other in a kind of cancerous symbiotic relationship, where each enables the other to grow uncontrolled like undiagnosed tumors, until they ultimately kill the host (the $IMFS):

The second frame is how it operates under extreme stress. This has happened twice. The first time was following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and the second time was last year, with the central bank conducting quantitative easing, stimulus, liquidity and bailout operations as a kind of monetary life support for a broken system. The central bank expands its balance sheet, pushing out new base money to fill the cracks in a broken credit money system:

The third frame is where the government reclaims the power to print money from its central bank. It’s still the Fed doing the printing, but the USG is now in control, makin' it rain fresh base money, trillions at a time:

The fourth frame is full-blown hyperinflation. Debt and savings are erased in real terms. Credit money is gone, and all money in circulation is base money at this point:

And the fifth frame represents the emergence of Freegold:

An important distinction in these images is the difference between credit money and base money. In the first frame, the small circle in the center represents base money, just sitting there, hardly moving. The two outer rings are credit money flowing through the system. And in the last two images, the vinyl-record-looking disc is all base money.

I debated the best way to explain the difference here, and after reading that Daniel Amerman article someone linked the other day, I decided on a method that would also help me explain what I think he was trying to say (more on that later).

All money today is bank liabilities.

There are two kinds of banks, and two kinds of bank liabilities.

The two kinds of banks are commercial banks and central banks, and the two kinds of bank liabilities are commercial bank liabilities, and central bank liabilities.

Sorry to spell it all out like a 4th grade teacher, but it's a really simple concept that will help you understand so much about the monetary system once you internalize this difference:

Base money = Central bank liabilities

Credit money = Commercial bank liabilities

And just to be clear, physical cash is a central bank liability. Central bank liabilities are physical cash, commercial bank reserves, and money held by the USG in its account at the Fed (the Treasury General Account or TGA).

This gets to some of the confusion surrounding the Amerman article which I'll get to in a minute, and the debate over whether the Fed is technically "printing money" when it does QE or various other balance sheet expansions. Trust me, both sides are explaining the same thing in different ways. Both are correct insofar as they are useful, and both are useful to some degree in explaining different things.

Banking in the modern world is a complicated business, but understanding it from a big picture perspective doesn't need to be complicated. So while my definitions and explanations may differ from others, I'm always happy to explain the differences, and to explain how mine are more useful and therefore better. :D

So, getting back to base money being central bank liabilities, I take it even further and say that central bank liabilities are base money, thus the equals symbol (Base money = Central bank liabilities). Some would say that all base money is CB liabilities, but not all CB liabilities are base money. And you know who would say that? Yup, the Fed.

Here's a quick primer on the common base vs. credit monetary aggregates, or "M"s. People often use M0 to designate base money, but M0 is not the monetary base (MB). M0 is physical cash outside of the banking system, and it is only part of MB. MB, the technical monetary base, is physical cash plus "Federal Reserve Bank credit (required reserves and excess reserves)." So, technically, what the Fed considers the "MB" is all of the Fed's own liabilities except its liabilities to the USG. And commercial bank liabilities (credit money) are M1-M3*. MZM is money of zero maturity, or basically money on demand. It's what I refer to as the effective money supply. (*Note that physical cash outside of the banking system is included in all aggregates.)

Here's a handy table courtesy of Wikipedia:

This table should include all types of money, except assets like stocks and bonds which are clearly assets. It should include all bank liabilities, from both kinds of banks. And it does, except for CB liabilities to the USG held on account at the Fed.

That's the United States Government's main checking account. Its balance is currently around a trillion dollars, and was recently as high as $1.8T. That's clearly money of zero maturity or money on demand, yet it's not even counted as part of the money supply. And that's because it doesn't quite fit either category. It's a checking account, so it should be in MZM, but it's actually Federal Reserve bank credit, which is included in MB but excluded from M1-M3 and MZM. It should probably have its own category, but it doesn't, perhaps because it only really became an issue recently. Here's a chart of the USG's checking account balance going back 35 years:

There are lots of ways to describe what's happening in that graph. You've probably heard one of them over the past year that when the TGA balance goes up, it is draining money from the banking system. Another way to look at it is that the USG is providing needed collateral (Treasuries) to the banking system.

I think the most useful way to think about what's in that graph right now is the way MMT describes how money flows through the USG. In essence, the USG spends money into existence, and taxes or borrows it out of existence.

I'm talking about credit money here, commercial bank liabilities. If you add them all up, you come up with the aggregate number of commercial bank liabilities (credit money) in existence at any moment in time. Let's call it [M3-M0]. That's M3 minus physical cash in circulation (because physical cash is technically base money).

When the USG takes in money by taxing or borrowing it, that same amount of commercial bank liabilities disappears from the banking system. So, if the USG takes in $500B, we should see the TGA balance go up $500B, and the credit money aggregates (M1, M2, M3 and MZM) drop by the same amount.

Then, when the USG spends that money, we should see the TGA balance drop and the credit money aggregates go back up. So, the USG taxed or borrowed credit money out of existence, and spent it back into existence.

This is because the USG's bank is the Fed, which is a central bank, not a commercial bank. Fed liabilities are base money, and commercial bank liabilities are credit money. So when someone with a balance at a commercial bank transfers money to the USG (to pay for either taxes or Treasuries), the commercial banking system no longer owes that person a dollar, that liability to that person has been transferred and is now a liability to the USG. But the USG's bank is the Fed, and the Fed's liabilities are base money, so the credit money in the overall banking system simply vanishes.

What happens is the USG credits that person's tax account or issues him, her or they a Treasury, but that's not something that happens inside the banking system. Inside the banking system, the commercial bank deletes its liabilities to that person, and the Fed debits reserves (Fed liabilities) from the commercial bank, and credits them to the USG.

When the USG spends money, the reverse happens. Some lucky individual gets a check from the Treasury and deposits it in a commercial bank. There are no commercial bank liabilities to transfer since the Treasury check is drawn from a central bank account, so the commercial bank creates new liabilities by crediting that person's account. The Fed then debits reserves from the TGA and credits them to the commercial bank in exchange for the check.

Understand, this is all just bookkeeping. Nothing is actually physical moving around. Banks are simply communicating with each other, and they are deleting, creating, debiting and crediting their own liabilities on their own books in a coordinated manner. A commercial bank deletes liabilities to a customer, the Fed debits liabilities from that bank and credits them to the TGA, another commercial bank creates liabilities to some government stooge, and the Fed debits liabilities from the TGA and credits them to the stooge's bank.

If you're still with me, the next thing you need to understand is another insight from the MMT crowd. And it's that the USG is not like you and me. Its ability to spend is not nominally constrained by its checking account balance, its ability to borrow, or even its ability to "earn" (i.e., tax). The presumed (nominal) constraint we've been following for decades is merely an illusion, because in extremis, the USG can spend money into existence. It's what we call printing. And if there's no (nominal) constraint in extremis, then there's no (nominal) constraint. Of course MMT now acknowledges the theoretical concept of an inflation constraint, but they don't seem too worried about it.

It follows that if there is no link of constraint between income and spending as far as the USG is concerned, then they are not connected. They are separate operations that don't need to happen in any certain order, or at all in the case of income. In other words, the USG can spend first, and fund that spending later, or not fund it at all. In extremis, that's what will happen.

The way to visualize this from a bookkeeping perspective is that the USG will write a check and some stooge will deposit it in a commercial bank. The commercial bank will credit the stooge's account with its own liabilities, creating credit money from thin air. Then, in exchange for the check, the Fed will credit the commercial bank with reserves (Fed liabilities) that it creates from thin air because the USG's checking account is empty. The USG's checking account is empty because no one can pay taxes or buy Treasuries anymore due to very high consumer price inflation.

The Fed will then need a (quote-unquote) "asset" to balance against the new Fed liabilities it just issued to the commercial bank, for bookkeeping purposes. So the USG will issue an IOU (a Treasury) to the Fed which the Fed will hold as a reserve asset to balance its books.

See what happened there? The USG issued a check to a stooge and an IOU to the Fed, and in the process it printed its own money. It was still the banks that created spendable money units from thin air, but it was the USG that forced the printing. The USG spent money into existence, without taxing or borrowing any money out of existence.

I should note that the Fed is not really allowed to directly fund the USG. All that means is that, when it does, it needs a middleman to buy the Treasuries first (the primary dealer banks), and then it buys the USG debt from them and calls it QE or whatever it wants. So this is not a de facto limitation, it is merely de jure, which of course means it can be changed at a moment's notice, or even retroactively in extremis. And if it doesn't exist in extremis, then for all intents and purposes it never really existed at all.

Something else I should note here is that the banking system is a fractional reserve system, where the reserves are base money or central bank liabilities. What this means is that in normal credit money transactions between non-government entities, the amount of base money needed is a very small fraction of the amount of credit money changing hands. Normal transactions are netted out, and only the small imbalances that remain require base money for interbank clearing.

Government spending is different in that every dollar the government spends comes with a full base money unit, a Fed liability. This is the mechanism by which the money supply is converted from mostly credit money (as shown in the first frame) to entirely base money (as seen in frame 4). Eventually, the government stooge will cash his check rather than depositing it, because cash prices will be lower than other forms of payment.

Getting back to the USG's checking account balance, which currently stands at just under a trillion ($925B), this is all base money (Fed liabilities) that already exists. The Fed has already "printed" it. And while it doesn't show up in the official money supply aggregates, it does show up on the Fed's balance sheet. And that's just the general account. There are other government accounts that probably add up to another half trillion right now.

In fact, the Fed's balance sheet has grown by 86% since the beginning of 2020. It was $4.17T at the beginning of 2020, and today it's $7.8T, so almost double. That means almost half of the US dollar base money in existence (46.5% or $3.63T) was printed in the last 14 months. And at least 40% of that went right into USG coffers. In other words, 18.6% (46.5% x 40%) of all of the base money in existence was printed by the Fed, for the USG, in the last 14 months. And half of that (more than $700B) was spent in the last three months, since January 20th, with more than $400B going to those $1,400 stimulus checks. Here's what it looks like on the Fed's balance sheet:

And here's the TGA balance again:

I wanted you to have a way to understand that graph (as the USG's checking account balance), and now that you hopefully do, I want to tell you that it doesn't really matter to me in the way you're probably thinking it does. I don't care about the raw numbers that have already been printed. I don't even care very much about why we see that spike in the last year (because we'll probably never know), or how fast it's dropping now. And I noted four distinct phases in red, but only to make note of them. I don't know what they mean, and haven't given it much thought (yet).

I can't tell you why we had that spike up to $1.8T in July because no one knows for sure. There are some possibilities related to the banking system. For a while there was even a theory that Trump was building a war chest of cash to spend right before the election to help him get reelected. I never thought much of that theory. Perhaps it had something to do with COVID. I don't know what the answer is, and it doesn't really matter to me at this time or in the context of this post.

What it does show, in my opinion, the part I circled in red, is how the income process is separate from and detached from the spending process. It is linked through bookkeeping by the Fed and the illusion of nominal constraint, but I think we can see that whatever drove that spike, it had little to do with spending. And when that plunging line hits zero and the USG keeps spending at its current pace, it will then be clear that the spending process is separate and detached from the income process, just like MMT says.

This isn't new. They were always disconnected, because if they can disconnect in extremis, then they were never really connected to begin with. So it's not that that changed, it's just that we're finally here where we get to see it in action.

This brings me to my update:

Speaking of hyperinflation, there was some discussion recently about FOA's house story, where the seller had to keep raising the price, and I wanted to add a few thoughts that I didn't see covered.

tEON wrote, "the market can generally freeze-up, as prices fluctuate between purchasing and closing dates." This is probably true during the worst of it, so FOA's story is more of an allegory than a description of reality. The raising of prices we see now is more of a "hot market" phenomenon than what FOA was describing. The market right now is a "hot market" or a "seller's market" or even a bubble. In hyperinflation, or even after, it will be the opposite of a hot market or a bubble, and it certainly won't be a seller's market.

One reason is that one of the things that happens in hyperinflation is that credit disappears, and things like houses drop to their cash price even as the nominal price is rising. No one will be going to the bank for a home loan during hyperinflation.

Another thing that happens is that there’s a shortage of cash relative to the nominal prices of things. So there’s no credit, and not enough cash, even as theoretical prices are rising.

Here's the quote from FOA:

---- "Honey, I talked to Fred again, he can't sell his house! Poor guy, he has had it up for two years now and has to raise his asking price again. No takers, yet. The last couple was just about to close but took a month too long; they almost got the cash together, too. He backed out to raise the asking price, again. Oh well, that's not so bad, we had to jump ours up three times before selling." ----

See? They couldn't get the cash together in time. No credit and a shortage of cash.

Now to the Daniel Amerman article. Kansasnate linked this article titled, Counterfeiters, Con Men, Mass Illusions & Funding The National Debt, and a number of comments ensued.

Hans wrote:

"From the Amerman article:

“What this mean is that much of the growth in the national debt was being temporarily funded by the U.S. Treasury itself, in a self-funding loop of sorts. The broker dealers bought the $1.6 trillion in debt as issued by the U.S. Treasury. The Treasury deposited the $1.6 trillion in its general account at the Federal Reserve. The Fed took the $1.6 trillion – which was a debt that it now owed the Treasury – and used those borrowed funds to buy the new debt from broker dealers. So, the Fed was the using the money borrowed by the Treasury to finance a big chunk of the growth in the national debt. Temporarily.

I know, I know, it sounds obscure and thinking through those loops can give a person a headache. But it matters, because it is a very dangerous and unstable way of funding the national debt.

The problem and the danger is that the Treasury borrowed the money in order to spend it. The Fed doesn’t have the money anymore – it already spent it all on the funding the national debt. So, when the Treasury wants its money – the Fed either has to borrow the money from someone else, or we have a BIG PROBLEM.”

The FED has to borrow the money from someone else? This sounds like the complete opposite of my understanding that the FED can just create new base money units (bank reserves) that can then be spent by The Treasury or used to buy USTs from the primary dealers. This would be the fusion of base money and credit money that FOFOA has put into the Go Full Retard category. Am I off base here?"

Bip wrote:

"Hans, if I have it mildly right, I think Amerman’s gist is that the Fed will indeed have to print, and that’ll be noticed by people watching for printing, but in the meantime this other mechanism is enabling the Fed to go to extremes before people even realize how far it’s gone."

attitude_check wrote:

"Hans,

Unlike commercial banks that can lend money into existence, the Fed cannot. Only the US Treasury can do that. The US federal debt is financed with Bonds, that have to be purchased. If commercial banks purchase them, then these become banks assets can then the be levered ~10x times by the commercial banks. The Federal Reserve is prohibited from directly loaning money I believe to anyone excepted Federal Reserve Banks, and even then only collateralized loans."

And Hans replied:

"@attitude_check

Hmmm then what is creating bank reserves to buy USTs from commercial banks defined as? It simply makes it so commercial banks can purchase the next batch of USTs from The Treasury. I understand it’s not credit money but this statement simply doesn’t make sense to me:

“The problem and the danger is that the Treasury borrowed the money in order to spend it. The Fed doesn’t have the money anymore – it already spent it all on the funding the national debt. So, when the Treasury wants its money – the Fed either has to borrow the money from someone else, or we have a BIG PROBLEM.”

So if The FED spends The Treasury’s checking account buying bonds… what happens? How is the checking account replenished? It seems to me the statement is just bunk to begin with. The FED wouldn’t use The Treasury’s checking account to perform QE. They’d just create to bank reserves and swap them for USTs with the primary dealer banks as they always do."

As I said above, what with repos, reverse repos, supplementary leverage ratios, IOR, IOER, the FFER, YCC and on and on, banking in the modern world is a complicated business. And Daniel Amerman apparently capitalizes on that. He seems to think understanding what's happening should be just as complicated, but it's really not.

Furthermore, I think Hans is right, and Amerman screwed up that paragraph he quoted. Let's break it down. I'll paste the full quote from Hans' first comment, and add my comments in red with brackets:

What this mean is that much of the growth in the national debt was being temporarily funded by the U.S. Treasury itself, in a self-funding loop of sorts. The broker dealers bought the $1.6 trillion in debt as issued by the U.S. Treasury. [Treasuries purchased this way are purchased with base money only, meaning Fed liabilities. The bank's credit money, its own liabilities, remains untouched. So the Fed's liabilities to the bank are transferred to the USG, and the Fed now has liabilities to the USG. Where those Fed liabilities used to be on the asset side of the bank's balance sheet is where the Treasuries now sit.] The Treasury deposited the $1.6 trillion in its general account at the Federal Reserve. [That's one way to put it. Another is that the $1.6T in Fed liabilities to the bank were debited from the bank's account and credited to the TGA, a simple shift of Fed credits (base money) from the bank's account at the Fed to the Treasury's account at the Fed.] The Fed took the $1.6 trillion – which was a debt that it now owed the Treasury [the reason they're called "liabilities" is because they are technically a debt owed by the bank to the account holder. When you deposit a dollar bill in your bank, your bank credits you with one of its liabilities, i.e., it owes you a dollar, but bank liabilities actually are dollars, so it's kind of redundant to put it this way.] – and used those borrowed funds [he's calling them borrowed funds because a deposit is essentially a loan to the bank. This is semantically confusing.] to buy the new debt from broker dealers. [Here's where he goes wrong. When the Fed buys a Treasury from a bank, that Treasury goes from the asset side of the bank's balance sheet to the asset side of the Fed's balance sheet. And on the bank's balance sheet, the Treasury is replaced with a Fed liability. He seems to be saying that's the same Fed liability sitting in the TGA, but it's not. If it were, then the TGA balance would have to drop when the Fed bought the Treasuries from the bank, but it doesn't. It doesn't disappear from the TGA or the Fed's own balance sheet. This is QE, the Fed expanded its balance sheet which created a new liability to buy the Treasury from the bank.] So, the Fed was the using the money borrowed by the Treasury to finance a big chunk of the growth in the national debt. [This is wrong.] Temporarily. [Supposedly temporarily, but only if the Fed can at some point unload $5T in USTs on the open market, in addition to whatever the USG is selling at that time. No, there's nothing temporary about it except the illusion.]

I know, I know, it sounds obscure and thinking through those loops can give a person a headache. But it matters, because it is a very dangerous and unstable way of funding the national debt.

The problem and the danger is that the Treasury borrowed the money in order to spend it. [This is true to an extent, but what's confusing about it is resolved by the MMT view that Treasury borrows credit money out of existence, and spends it into existence.] The Fed doesn’t have the money anymore [he's conflating credit money with base money here, and remember, credit money was never involved. The USG only ever took in base money from the bank. If the buyer had been a non-bank entity, then credit money would have disappeared, but because it was a bank who bought the Treasuries, credit money remained untouched] – it already spent it all on the funding the national debt. [No, it created new base money to do that.] So, when the Treasury wants its money – the Fed either has to borrow the money from someone else, or we have a BIG PROBLEM. [Here's where the money supply issue comes into play. Perhaps that's what's driving this (IMO) mistake. The Treasury's "money" is still right there on the Fed balance sheet. It's Fed liabilities sitting in the TGA. They're simply not counted in any of the "M"s. And because they were purchased by a bank and not a non-bank entity, no credit money disappeared. But when the USG goes to spend that money, the Fed will simply transfer its liability from the TGA to the recipient's bank, and that bank will credit the recipient's account thereby creating brand new credit money. So, you see, when banks buy Treasuries, and they are not then resold to non-banks, the credit money supply expands when the USG spends.]

This specific "mistake" aside, I do think I understand what Amerman is trying to say. He draws a distinction between whether we're seeing a "shell game Ponzi scheme" crime in progress, or whether it's simple money printing. It's both, and they are not mutually exclusive. In addition to the monetary expansion that's happening (the money printing), there are also some very complicated shell game Ponzi scheme things happening, which I've written about before.

You may remember the bond basis trade run by Relative Value (RV) hedge funds which Zoltan Pozsar wrote about, and I wrote about here. That basically had hedge funds funding the USG using really big leverage. Or the exclusion of Treasuries from the Supplemental Leverage Ratio (SLR) which I wrote about here, which essentially allowed Treasury to fund itself through commercial banks without needing new base money from the Fed. That program expired this month.

The point is, there are plenty of complicated things going on that could blow up and cause a financial crisis, and I think that's what Amerman was calling a "rogue moon zipping past our planet" when the USG started drawing down its checking account balance. But like I said, the base money is already there, and the commercial banking system simply creates new credit money when it credits anyone's account who deposits a government check, or anyone who had a stimmy magically appear in their account.

No one had to go hunting under shells to find that money, but there's plenty else that could go wrong. And that seems to be his focus, what could go wrong. But after clicking through a few of his articles, I got the impression that he may be missing the forest for the trees.

I'm not trying to pick on him, because I like him. But he came up in the comments here, and after reading a few of his articles, he turned out to be useful for this post. So apologies if you're reading this Daniel.

It seems to me that he's stuck in frame 2 thinking, which has all the complicated trees that he's really good at explaining…

…but without looking at the forest as a whole, I think he might have missed that, "with no big public announcements or widespread public understanding" (to use his words), we quietly slipped into frame 3:

He acknowledges that it could happen, but perhaps doesn't see that it already has. Here's a quote from one of his other articles:

"Even with no big public announcements or widespread public understanding, nonetheless, if reserves-based monetary creation is quietly replaced with MMT or some other variant of straight up money creation, then everything changes for all of us, right then, when it comes to our financial futures. […]

Higher rates of inflation return - in a potentially major way. It could take a while for this to develop, and things could look relatively normal in the interim - or it could happen relatively quickly. That said, the moment that reserves-based monetary creation is potentially replaced with actual MMT, then all rational medium and long term market expectations change, even if the immediate effects are not necessarily obvious. If this happens, and someone is not yet prepared, this will be a time to move fast to change expectations and strategies.

Even though he retired as Fed chairman many years ago, what is currently dominating the economy and the markets are two radical economic experiments, that Benjamin Bernanke first began proposing long ago. One is the Federal Reserve's use of reserves-based monetary creation, which was Bernanke's baby, and he fundamentally changed the U.S. economy, monetary system and financial markets when it was implemented. The other is showering the economy with "helicopter money" in the event of crisis, which sounded like a crazy, fringe theory when Bernanke first proposed it - but it is now official government policy and the economy is dependent upon it. Showering the population with repeated rounds of money that are funded by running up the national debt, with the rapid increase in the debt itself in turn being primarily funded by the Fed's use of reserves-based monetary creation - has never happened before, indeed we have never seen anything even close to this before…

How the United States government has been attempting to contain the current economic devastation could be called off-the-scale insane by the ordinary standards for governments over the decades and the centuries. A government simply doesn’t create dollars equal to close to a quarter of the size of the economy, taking on more national debt in inflation-adjusted terms in a single year then they previously had over two entire centuries, in order to flood the population with repeated rounds of big checks. […]

Of course, this won’t necessarily happen. Reserves-based monetary creation has held together for 13 years now, and it could yet continue to hold together for this now second round of the containment of global financial crisis…

The distinction he draws between "reserves-based monetary creation" and "actual MMT" is a technical one. But I would argue that the true distinction, the de facto distinction, is political, not technical. So, while he acknowledges this as one of several possible "paths," he misses that we're already on it.

Now, I want to reiterate that my graphic is not meant to show causation. This includes moving from frame 3 to frame 4. What you see in frame 3 does not cause the move to frame 4, but it makes it possible. It sets the stage for it. It's a powder keg ready to blow, but it still needs a spark.

I don't know what that spark will be. It could be something that spooks the markets, or something that panics the general population. Maybe both, but if I had to pick one thing to watch, I'd watch food prices at your local supermarket. Unlike lumber, when food prices jump, that will be something everyone notices. This isn't 2020 anymore. This is 2021, and when we finally get a big bout of consumer price inflation mixed with a little panic, some food hoarding, and some insane totalitarian government knee-jerk response, which will obviously include another emergency spending package, that might be it.

Sincerely,

FOFOA

5/6/21

I responded to a few questions in the comments under the Hyperinflation Update post, and since not everyone follows the comments, I thought I'd put them in a post.

Yakalex asked:

"Fofoa,

Thanks for explanations.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/stunning-divergence-latest-bank-data-reveals-something-terminally-broken-financial-system

From zerohedge article above – do I understand correctly, that current difference of almost $2.445 trillions between deposits and loans (MMT postulates that deposits = loans) at 4 largest Banks, represents real money created into existence by Treasuries since 2008 against central bank liabilities, without help from commercial banks?"

And here was my response:

Hello Yakalex,

MMT says that loans create deposits, not that the amount of loans and deposits should be the same. The purpose of that statement is to explain that a bank doesn't need someone to deposit money before it can loan it out. The very process of loan origination creates the deposit out of thin air. This is true, and that ZH article is incorrect when it says that loans creating deposits, "the anchor theory of MMT on which all its other laughable theories are built," is false. It's not false, it's true.

See, it's in my first frame. Loan origination and deposit creation:

"Deposits" in the MMT lexicon are basically synonymous with "commercial bank liabilities" in my post, which are synonymous with "credit money" in my post. So "deposits" = "credit money" would be the correct accounting identity, not deposits = loans. Loans create deposits, but not all deposits come from loans.

Also, while I'm on this topic, don't confuse "credit" and "credit money" in my lexicon. They are different things. When I say "credit" will disappear in hyperinflation, that's different from saying "credit money" will disappear. Credit (lending) will disappear first, but "commercial bank liabilities" aka "credit money" will still be circulating.

Eventually, reserves will nominally overwhelm assets on the commercial banking system aggregate balance sheet, and at that point "credit money" and "base money" will be equal. In other words, MB will be equal to MZM. That's frame 4. Once we reach that point, it'll probably switch to physical cash only pretty quickly, and then M0 will be the entirety of MB which will be the entirety of MZM.

So, when MB equals MZM, "credit" (lending) will have disappeared, and when M0 equals MB and MZM, then "credit money" will have disappeared. So credit goes first, and that's because credit can only exist if interest rates can be higher than the rate of price inflation. They can to a point. Not sure what that point is, maybe 100% or 200% APR at the most, under certain conditions like short term collateralized loans. But beyond that, it just becomes unserviceable and a guaranteed loss for the lender. So once consumer price inflation gets above that, credit will disappear pretty quickly.

Here's what a commercial bank balance sheet looks like under normal conditions, like in frame 1, say from the 1970s until 2008. The liabilities on the right are also known as deposits aka credit money. And on the assets side, the Rs are Reserves, or central bank liabilities aka base money, while the As are Assets, or loans in MMT terms:

Assets | Liabilities

RRAAAAAAAAAAAAA|L L L L L L L L L L L L L L

Those are fractional reserves. See how there are 2 base money reserves and 12 assets? That's a fraction of 1/7th, or MB=2 and MZM = 14. That's frame 1.

Then, as that ZH article shows, lending basically flattened after the GFC and QE took over. Now the commercial bank balance sheet looks more like this:

Assets | Liabilities

RRRRRRRRRRRR AAAAAAAAAAAAA |L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L

See how the fractional reserves are now 50%? Those are the excess reserves created by the Fed and spent into existence by the USG. That's what frame 2 does to the banking system.

Frame 3 will keep expanding the Rs and reducing the fraction until hyperinflation erases the As altogether, in real terms. Then it will look like this:

Assets | Liabilities

RRRRRRRRRRRR RRRRRRRRRRRR |L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L L

That's frame 4. Credit is gone (no more As), but credit money still exists (the Ls are still circulating).

From that point on, there are different possibilities as to how it unfolds in terms of physical cash versus electronic debits or transfers. My thought is that if base money (CB) digital dollars were fully rolled out before HI, then it's theoretically possible it stays electronic. But we're still far from there today. Years away I would say, if not more.

It's not whether it's possible or not, or whether it's already on the drawing board or in the works, it's whether everyone is already using it. I can imagine the USG trying to push out some really big numbers electronically, but unless it can circulate through the economy, what's left of it, there won't be the demand for it. They'll be pushing on a string.

What good is a trillion dollars unless you can hand it to your daughter and send her over to the baker for a loaf of bread and some muffins? We aren't even close to there yet. I'm talking zero transfer or transaction costs or fees, just like cash, zero clearing time, just like cash, and no middleman, peer to peer as the kids like to say, just like cash.

Some of us don't even have smart phones. And that's another issue. If your cash is dependent on the internet or electricity, then the government can render it useless by turning off the internet or the power in your area. Not so with physical cash.

So while the technology for true digital cash may theoretically exist, if everyone's not already using it and totally comfortable with it before HI, then it's not really up to the preference of the Fed or the USG at that point. You need demand for your money, even in hyperinflation, and if you're trying to push out something new, no matter how big the numbers, it's not going to buy you what you need. So I think they'll be forced to print physical cash with lots of zeros to keep their stooges doing their bidding for as long as possible.

So yes, to answer your question, that is real money that was created by the Fed and spent into existence by the USG. It doesn’t matter if the Fed is buying old Treasuries or new, it still expands the effective money supply (MZM) when the USG spends credit money into existence. So that's all credit money too, it just wasn't loans to the economy. It was "QE", which was, in effect, a loan from the Fed to the USG, which became MZM once the USG spent the money.

I'll leave you with some food for thought. You've probably heard of YCC or Yield Curve Control. That's when the Fed controls the yield curve so it doesn't get out of control and blow the whole effing system to smithereens. Some say they're already doing it to some extent. But here's the thing. Nosh once explained the difference between QE and YCC to me thusly: A critical distinction between QE and YCC is that QE is about supplying a fixed amount of money for buying assets at any price. YCC, on the other hand, is about supplying an infinite amount of money to buy assets at a fixed price. So, to quote Nosh, "YCC is QE on steroids if you understand the technical dynamics."

Sincerely,

FOFOA

"Thanks Fofoa for your explanations.

From memory. Before 2008 USG kept its collected funds at special accounts with some largest commercial banks. Introduction of excessive reserves and interest on excessive reserves to fight GFC resulted in creation of TGA at FED and closing of accounts with commercial banks. In addition, Congress introduced limit on TGA balance increase calculated as some percentage from previous average for the year. As result, TGA balance started growing with speed limited by Congress.

So, actually total deposits in commercial banks represent total liquidity in the economy, balanced by liabilities of commercial banks and USG (TGA at FED?)?

From ZeroHedge graph [“Big 4” bank total loans and deposits] – Aggregate Deposits are $6.9T and Aggregate Loans are $3.546T. Hence Aggregate USG liabilities should be $3.354T. But we know that at maximum TGA was $1.8T."

Hello Yakalex,

The TGA balance has no relation to those aggregate loan and deposit numbers. The TGA balance is not going to show up in the aggregate deposits until it is spent by the USG. What you're calling "USG liabilities of $3.354T" would have been spent into existence by the USG over the past 12 years. They represent past printing, past QE by the Fed, past spending-credit-money-into-existence-without-taxing-or-borrowing-it-out-of-existence. It has no relation to how much money was held in the TGA at any given point in time. It's an aggregate of credit money that the USG spent into existence over time.

Here's the graph you're talking about:

All it says to me is that the aggregate commercial bank balance sheet expanded normally (i.e., through lending) before 2008, and since then it has been expanding a different way, through QE or raw printing. Yes, all that QE money does end up in the MZM or effective money supply because the USG spends it into existence without taxing or borrowing it out of the MZM or effective money supply. You can see it in that graph.

In terms of my graphic, you can see the shift from frame 1 to frame 2 that happened in 2008 in that graph. The difference is that the Fed was controlling that printing for the last 12 years, and was doing it for reasons related to the financial system, to keep rates down or prices up or to add liquidity or whatever. What's changed now with the shift to an MMT-minded USG that wants to print as much as possible and isn't afraid of inflation or hyperinflation is that the printing is no longer going to happen for financial system management reasons only. It's now happening for political reasons. That's the shift to frame 3 that this post is all about. Notice also that Obama's Fed Chairman is now Biden's Treasury Secretary. The printer in chief has been promoted to the spender in chief, and she know how to make it happen.

But don't let the technical mechanics of the TGA confuse you. The TGA is actually a network of Treasury-approved commercial banks including the ones in that graph, and others around the world. They are "Treasury-designated depositories" and they accept over-the-counter physical cash, check and wire transfer deposits on behalf of the USG/Treasury, but they don't appear as deposits on their own balance sheets. They only appear as liabilities on the Fed balance sheet. Remember, it's all just bookkeeping. Here's the TGA on the Fed balance sheet, and you can also see the "other" accounts which I mentioned which have another half trillion in them as of April 21st:

As I keep saying, it's complicated business, but understanding what's happening from a big picture perspective doesn't have to be.

When money goes into the TGA, credit money goes POOF because the TGA-approved commercial bank doesn't put it on its own balance sheet, only the Fed does (as a liability to the USG). Then when the USG spends that money, credit money is created when the bank receiving the USG check credits the depositor's account. If the Fed buys Treasuries, even old ones, it creates new "excess reserves" in the commercial banking system that become new credit money when the commercial banks use them to buy new Treasuries and the USG spends that money. That's how the aggregate commercial banking system's balance sheet has been expanding since 2008, as seen in this graph (here it is again):

All that money printing wasn't really price inflationary, though, at least not for consumer prices. Right now, however, we have a stagnant or even depressed economy and a government driving the printing for political purposes. That's starting to cause inflation which is devaluing the currency. But remember, hyperinflation is a feedback loop that begins with the currency devaluing which causes the printing, which causes the currency to devalue even more, which causes even more printing.

It's the devaluation that's driving it, and the printing is just making it worse, like trying to put out a fire by dousing it with gasoline. But the printing is not driving it, it's trying to keep up. That's why there's a shortage of cash. If the printing was driving it, then there would be a surplus of cash bidding higher than asking prices. Instead, prices are outrunning the cash.

I mention this because someone just said that $1.8T is not enough to get his attention, but $18T would be. That sounds like someone who's expecting the printing to start the hyperinflation. That's not how I see it. The $1.8T continues to show the USG's new willingness to print, and that's what's important, not the number. The real printing will start once we have the systemic shock, whatever that is, in an inflationary environment with a disabled economy.

I mentioned YCC in my last comment. Here's what it could look like: Something happens and the USG starts emergency knee-jerk printing to save everyone from starvation. The bond market starts imploding so the Fed starts YCC. You'll hear everyone talking about YCC, but that's not what's really happening. What's really happening is full-blown actual MMT under the guise of YCC.

This is the Catch-22 the Fed finds itself in right now, and it's the classic sacrificing the currency to save the system. If they let the bond market implode, then the system (meaning the commercial banking system) implodes, but by "controlling" the curve through the infinite base money printing of YCC, they nominally save the banks but destroy the currency. Meanwhile, the USG is spending all that infinite base money into existence in the effective money supply (MZM).

So don't worry about the TGA or the past printing. That's all water under the bridge. That's all stock, not flow, and it's all about the flow. To me this looks like the perfect storm. We have an MMT-minded government ready to spend for even the dumbest of reasons, so you know what they'll do when the shit hits the fan, right? Spend! On top of that, we have a disabled economy and a broken financial system. What more could you ask for? Ben Bernanke as Treasury Secretary? Gideon Gono?

Sincerely,

FOFOA

AuHiker wrote:

"Hi FOFOA,

In regards to the expansion of the aggregate commercial banking system’s balance sheet from 2008 – 2019 you commented:

“All that money printing wasn’t really price inflationary, though, at least not for consumer prices.”

Was this due to the fact that although M0 expanded with QE, the majority of this money remained in the financial sector, boosting up stock prices while M2 maintained its growth (more or less) at the same rate as before the GFC? This in contrast to the drastic rise in M2 since 2020 which we are starting to see translated in consumer price inflation?"

Hello AuHiker,

I guess there are two separate points to tackle here. Did the money remain in the financial sector? And if not, then why didn't in translate into consumer price inflation?

First, a simple concept. There is no money in the asset arena, what you're calling the financial sector. There are only assets, and there's an inflow and outflow of money. Sometimes that inflow is insufficient to support both the outflow plus the addition of new assets, like new IPOs and new bonds, etc. The "outflow" of money is when people sell assets for money.

So, the answer to did this money remain in the financial sector is no. When the Fed buys assets, the money flows through to the seller or issuer of the assets. Even though it did contribute to the boosting up of asset prices, there's still no money in those assets. It flows through.

It is true that the Fed only prints base money (MB), and I've explained how that becomes part of the effective money supply (credit money) when the USG spends it. If you want to see how much fresh base money the USG spent into the credit money supply since 2008, you just have to look at how much USG debt the Fed has on its balance sheet today, and subtract how much it had back in 2008. The answer is, the Fed held about $750B in 2008, and today it holds $5T, for a difference of $4.25T. That's a little bit more than the $3.354T difference in this graph, but the graph is only four banks, JPMorgan, BofA, Citibank and Wells Fargo:

So that's all raw money printing. In theory, raw money printing should be price inflationary, but not if the rest of the world is overvaluing your currency and causing you to run a perpetual trade deficit. That's why we haven't seen the consumer price inflation that would otherwise be expected.

Sincerely,

FOFOA

Jman1959 wrote:

"Fofoa,

“I mention this because someone just said that $1.8T is not enough to get his attention, but $18T would be. That sounds like someone who’s expecting the printing to start the hyperinflation. That’s not how I see it. The $1.8T continues to show the USG’s new willingness to print, and that’s what’s important, not the number.”

I see your point on our current printing not starting HI directly, but it seems like it has certainly caused significant inflation, which will drive people to spend money that they had previously been comfortable sitting on (as we see happening now in housing and other sectors). As you have said before, the USG doesn’t have to print another dollar for the currency to hyperinflate. So while it doesn’t lead directly to a HI feedback loop (even Volker era inflation was not HI), it seems like continued printing and the resultant inflation could set the stage for a huge increase in velocity, and that the combination of increased velocity, rising inflation, an adequate supply of dollars, and a rapidly declining economy could certainly kick off a dollar confidence crisis, especially given the limited options of the Fed to control it anymore. Am I off base here?"

Hello Jman,

Yes, hyperinflation includes an extreme velocity of money. But I view that velocity as an effect more than a cause of hyperinflation. People watch for increases in velocity as an indication of coming hyperinflation, or the reverse, they say how can we have hyperinflation when velocity is so low? I say, just wait, you'll see velocity turn on a dime once the hyperinflation starts.

And yes, hyperinflation includes lots of printing and lots of money. But same thing. I view that as an effect more than a cause of the hyperinflation. Like velocity, the rising quantity of money is part of the feedback loop that keeps it going, but again, people look for increased printing as a sign that hyperinflation is near, or the reverse, they say, $1.8T is not a hyperinflationary number, but $18T is. I say, just wait, you'll get your $18T once the hyperinflation starts. But it still won't be enough. By then you'll say $18T is not enough to get my attention, but $180T, now that would be some hyperinflation. See how this works?

People want to know how hyperinflation can happen here. They don't believe it can. They think that the US dollar is too big to go into hyperinflation. It's used globally, so there's just no way it could hyperinflate. You'd have to print too much money to drive up prices all over the globe. Hyperinflation has never happened in a global reserve currency, therefore it must be impossible. Smaller currencies hyperinflate against the reserve currency, so what's the reserve currency going to hyperinflate against? This is why I go above and beyond just predicting hyperinflation or repeating how it theoretically works. I try to show you how it's going to happen here and now in the global reserve currency.

I don't know if the printing so far is causing the inflation we're seeing. It probably has a hand in it, but there are many other causes in play right now as well. We have bubbles in almost everything, we have Chinese money driving up prices in certain sectors, we have people repositioning due to political changes. We have supply chains that have been suppressed for a year now. There are lots of things contributing to rising prices here and there, and they will all contribute to the ultimate demise of the dollar.

Yes, theoretically velocity alone could kill the dollar, but it won't. It's a whole bunch of things working together, and my point is that the stage is already set. I'm not looking for more printing, they're already doing it. Every new bill seems to cost $1.8T or $1.9T these days. It's like an acceptable price point. It's like the Overton window of MMT right now. It's like $89.99 instead of $90. Soon we'll break through the $2T barrier on a single bill and the MMT Overton window will shift. But it won't shift drastically, in orders of magnitude at a time, until hyperinflation causes it to.

You said the inflation will drive people to spend money they have been sitting on. Again, I see that as more of an effect than a cause, although yes, it is part of the feedback loop. I think that when that happens, hyperinflation will already be underway. I'm not sure this current inflation we're seeing will drive people to spend the money they've been sitting on, but hyperinflation will. As for housing, credit is still plentiful, so it's likely just a bubble combined with people fleeing certain locations and maybe some Chinese money coming in as well.

That doesn't mean it's far away. I think it could happen at any moment. All it will take is a spark, because I think the stage is already set in a way that it wasn't even a year ago. Yes, you're right, all those things you say are part of the feedback loop of hyperinflation, but to view them as a cause is wrong. Hyperinflation is not inflation on steroids. Hyperinflation is deflation with wheelbarrows. It's a bunch of bubbles popping simultaneously in real terms, including the currency itself.

Sincerely,

FOFOA

Yakalex wrote:

"Went to FRED site to check figures and ratio and was lost, because numbers do not correspond to what I was expecting:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20210311/

Reserve Bank credit (aka FED Balance) as of March 11, 2021 7,530,925

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTLL

Loans and Leases in Bank Credit, All Commercial Banks as of March 10, 2021 10,443,012

as of Dec 30, 2020 10,371,721

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DPSACBW027SBOG

Deposits, All Commercial Banks as of March 10, 2021 16,570,488

as of Dec 30, 2020 16,097.486

In addition, FED balance is not equal to Deposits – Loans."

Hello Yakalex,

The "FED balance is not equal to Deposits – Loans," but it is reasonably close, so perhaps we are forgetting something. Let's see…

The FED Balance (Reserve Bank credit) includes what's in the TGA ($1.31T as of March 10, 2021). And remember, what's in the TGA does not show up in Deposits until the USG spends it.

So, what we should expect to find (very roughly of course) is Fed Balance (Reserve Bank credit) minus TGA balance = Commercial Bank Deposits minus Loans.

Fed Balance – TGA = 7,530,925 – 1,310,273 = 6,220,652

Deposits – Loans = 16,570,488 – 10,443,012 = 6,127,476

That's pretty close! :D

Sincerely,

FOFOA

Hans wrote:

"I get that paying back a loan destroys credit money. But does defaulting on a loan really destroy credit money?"

Hello Hans,